Nieman Journalism Lab |

- On Adele Dazeem, Slate, and editorial ambivalence: “Our readers go low with us, and they go high with us”

- The newsonomics of Newsweek’s pricey relaunch

- ProPublica opens up shop with a new site to sell custom datasets

- Q&A: ESPN’s Henry Abbott on TrueHoop, serving readers, and the future of sports blogging

| Posted: 04 Mar 2014 12:06 PM PST If you watched the Oscars Sunday night, you probably saw John Travolta screw up the name of Idina Menzel as “Adele Dazeem”: It got lots of attention online, and Slate jumped on it with The Adele Dazeem Name Generator, which tells you how John Travolta might mispronounce your name. (If you’re interested, the Nieman Lab staff is made up of Jorja Brazent, Julian Edjans, Chantelle Orteez, and Jonah Warshington. Also, “Nieman Lab” is Niven Loing.) The story went insane on social media and became the most popular story in Slate history. Which led Slate editor David Plotz to tweet: That ambivalence, I’d wager, is a lot like the feeling some had in The New York Times’ newsroom when they realized the most popular Times story of 2013 was a dialect quiz made by an intern. Those reporters and editors get into the business to do certain kinds of work, but the factors driving today’s news web — the availability of analytics, the rise of social sharing, and what remains of the CPM-driven advertising model — mean it’s increasingly clear that popularity doesn’t always line up with the work you’d want mentioned in your bio. I emailed Plotz to get a little more about that ambivalence, and here’s what he had to say:

|

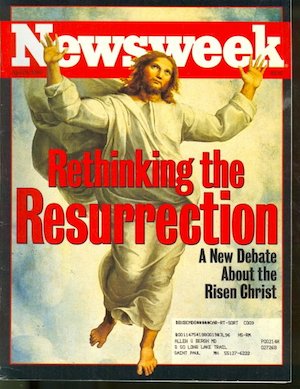

| The newsonomics of Newsweek’s pricey relaunch Posted: 04 Mar 2014 09:35 AM PST Maybe the third time is the charm. Three years before Don Graham and Jeff Bezos talked about selling and buying The Washington Post, the Graham family bid goodbye to its second favorite son, Newsweek. Sid Harman, then 91, optimistically bought it for a buck, taking on $50 million in liabilities and promising a rebirth. Within three months, Harman struck a deal with Barry Diller and Tina Brown merging Newsweek with The Daily Beast, creating an unusual creature that could not be easily cataloged.

A year later, acknowledging failure, IAC sold Newsweek — once a proud No. 2 to the inventor of the newsweekly, Time — for a pittance to IBT Media. “I wish I hadn’t bought Newsweek,” Diller said, calling weekly print in the digital era a “fool’s errand.” The buyer seconded that notion. “We are 100 percent digital company and so that’s been our forte,” said IBT CEO Etienne Uzac. “In the future there might be some opportunity for print but not right now.” The siren call of print, though, is just too seductive, even as each successive ownership has gotten a generation younger. Uzac, 32, and IBT cofounder 31-year-old Johnathan Davis share neither the name recognition nor the longstanding love of print with the Grahams, Harmans, Browns, or Dillers — but print beckoned to them nonetheless. This Friday, the new print Newsweek, which hadn’t been published since the end of 2012, hits the stands. Maybe “hits” is too strong a word. At a whopping $7.99 a copy, it should perhaps land on a soft pillow, the better to protect the paper quality that is promised to be twice that of long-time nemesis Time. It may seem like a turn of events around a familiar storyline: the reckoning of once-iconic news brands, national and local (“The newsonomics of the print orphanage, Tribune’s and Time Inc.’s”). In fact, the IBT’s Newsweek gambit is more interesting. It’s a mixmaster of many trends of our day, including the ascendancy of reader revenue models, the central place of powerful platforms in digital publishing, and the use of analytics to drive new news businesses forward. The Newsweek push and IBT Media’s wider efforts combine lessons from Vox Media, The Economist, The New York Times, and even Time. The newest Newsweek strategy is both old-fashioned and radical. It’s old-fashioned in the sense that it is reviving a ghost print brand with printing presses on two continents. It’s radical in its pricing. Even the high-flying, high-quality weekly New Yorker only charges about $79 a year, while Time goes for $30 and The (monthly) Atlantic for about $25. Newsweek is going way beyond those prices. The print launch is all wrapped up in a lovely package, led by magazine veteran Jim Impoco. In fact, that package — with design by Robert Priest and Grace Lee — seems almost anachronistic, a throwback to another era of plush and flush magazines. In a sense, the newest Newsweek is trying to create its own category: NewsLuxe. If $8 seems a bit rich for a newsmagazine, subscribers can pay the equivalent of a still-high $3 a week for a new subscription. The new Newsweek, I’ve found out, is joining the all-access parade with this planned pricing:

The pricing had better work. The Newsweek paywall is going up this week, as the print launch (party at SXSW) is readied. Davis, who also serves as chief content officer, says the business model is heavily dependent on reader revenue. He expects that 80 percent or 90 percent of the new Newsweek’s income will come from readers, with only 10 to 20 percent from advertising. Whether this experiment turns out to be a great new way to fund journalism or the makings of a spectacular failure, you have to give Davis and Uzac credit for rethinking old paradigms. They’ll tell you they didn’t expect to go into print. They looked at the low-priced print model they inherited — “the more you printed, the more you lost” — and figured the business is “upside down.” With the new high pricing, each copy printed, they say, will be profitable. To be sure, Newsweek isn’t planning on selling hundreds of thousands of print subscriptions. Its goal, says Davis, is 100,000 U.S. subscribers and 100,000 in EMEA (Europe, Middle East, Africa) within 12 months; other licensing agreements will produce other editions on other continents. Its initial press run: 70,000. That’s down from about 3.3 million at Newsweek’s height. The bet: that many of older Newsweek subscribers, longing to renew their habit, will re-subscribe. The company is poised to mine its lists of somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000. Those names and data have now passed through several owners and incarnations, so their reliability is a significant question for subscription conversion. While Newsweek will get lots of attention this week for its seemingly anachronistic print launch, its digital pricing also breaks new ground. It’s going to market with a metered paywall, one powered by Europe’s Piano Media, now making its first big foray into the U.S. after successful launches in central and eastern Europe and more western European publishers queuing up. The paywall isn’t unusual; the pricing is. Charging $39.99 for digital-only access is high, especially considering that the seeming competition, Time, can be gotten — in both print and digital — for no more than $30 a year. What makes the revivers of a ghost brand believe customers will pony up? “We’ll deliver the quality of a monthly every week,” says editor Jim Impoco. Impoco is a well known talent in the magazine world, with U.S. News, Fortune, Men’s Journal, and the short-lived but highly regarded Portfolio magazine among his career stops. That means investigative reports and storytelling and visuals that fit the quality of the paper they are printed on. Impoco’s acceptance of the Newsweek job was in part based on the place he believes it can occupy in the contemporary world, with more than 2 million Twitter followers. He’s assembled a talented staff of 30 full-timers, plus additional contractors. Impoco says he doesn’t believe that the star system is the new thing in digital news (“The newsonomics of David Pogue and the Pujols effect”). The star is the brand, the up-from-the-ashes Newsweek. Its New York staff is largely filled out, and its London newsroom got a jumpstart today, as it named Richard Addis to head up its EMEA edition, out of London. Addis is the former editor of Canada’s Globe and Mail and London’s Daily Express. Under Impoco, the new Newsweek should be an impressive, worthwhile read. The question is whether it can be sufficiently impressive to win large paying audiences fairly quickly. Even if it offers a lively product online, the paywall is sure to send many testers returning to the free Slates, HuffPosts and BuzzFeeds. The meter will allow some sampling, of course, but it is going to be tough to get readers to click that $9.95-for-three-months button, much less the $40-for-a-year one. What could determine the success or failure of the new Newsweek?

Newsweek is a big, splashy, upscale play. Everything about it — new redesigned print, atmospheric pricing, an early paywall — says premium, yet its young owners have little to no experience in the premium world. They may bring a refreshing skepticism about the way print magazines have long been done — the conventional wisdom of building a large, advertiser-satisfying subscriber base on cheap subs — but they may be getting in over their heads. There may be room for the new model — and kudos to the newest Newsweek owners for testing it. If it does work, experience tells us it’s likely to take several years to prove out, and that may test the financial limits of this bootstrapping effort. As we approach mid-2014, we’ve got Newsweek getting one more (maybe its last) chance at survival and Time shape-shifting once again, as Time Inc. spins off uncertainly into the publishing future. For a genre long known for cycling back to the same subjects over and over, the cover story of the year appears to be: Can Newsweeklies Survive the Digital Age? |

| ProPublica opens up shop with a new site to sell custom datasets Posted: 04 Mar 2014 08:03 AM PST Data is at the heart of much of ProPublica’s reporting. So why not try to find a new way to make money off of your franchise? With the launch of the ProPublica Data Store, the nonprofit is trying to see if it can turn one of its strengths into a potential revenue generator. The Data Store offers a selection of datasets — some for sale, with prices varying depending on the user, some free. The information in the store is a mix of raw data ProPublica has received through FOIA requests, data already available on the open web, and datasets that have been cleaned and prepared extensively by ProPublica staff for other investigations. While the raw and open datasets are free, the data cooked by ProPublica comes with a price tag attached. It’s a setup similar to NICAR’s Database Library, which offers journalists clean and formatted government data on things like plane accidents, federal contracts, and workplace safety records. For users wanting to get their hands on a state’s worth of data from ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs series, for instance, the cost varies: $200 for journalists, $2,000 for academics. Companies looking to use the data for commercial purposes have to negotiate a (presumably higher) price with ProPublica. Like any good business, ProPublica offers potential customers free samples of the data before they make a purchase. ProPublica has always encouraged a level of openness with its work, often making investigations available to others by Creative Commons, or building news apps that allow readers to play with data. The data store is an extension of that, but also a potential solution to a question many newsrooms face: how to extract additional value out of an investigation. But don’t expect the store to be a significant source of revenue, at least right away, according to Richard Tofel, ProPublica’s president. “It will take a while for us to see if that’s a serious revenue source or not,” Tofel told me. Tofel said the company has fielded requests for commercial use of its data in the past. He said that could be a source of business of the company, if the interest materializes. The broader goal of the data store, he said, is providing an easier way for people to access information ProPublica has at its disposal. “The net effect of this initiative is to make a lot more data publicly available without having to go through us,” he said. Scott Klein, senior editor for news applications at ProPublica, said one purpose of the data store was to create a standardized system for the flow of data through the newsroom. As a repository, the data store can be a resource to point journalists and academics to what records are available for free online. But Klein said the store also expands on the idea of encouraging others to build on ProPublica’s work. In building the data store, Klein said they wanted to develop pricing that would account for the hours of work his team put into the datasets while also being fair to journalists and academics. “It’s not uncommon for us to spend months cleaning and assembling datasets,” Klein said. There’s no revenue targets or other goals associated with the project. Both Klein and Tofel said they’re eager to see the response to the data store and if it can gain traction. Klein said he believes if the experiment is successful, one idea they could consider is à la carte datasets created specifically for others to purchase through the data store. “One of the ways of figuring out if there is a market for this, and how to serve this market, is to just try it,” Klein said. Photo of the Data Food Store in Molenbeek-Saint-Jean by Paul Keller used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Q&A: ESPN’s Henry Abbott on TrueHoop, serving readers, and the future of sports blogging Posted: 04 Mar 2014 06:30 AM PST The reason Henry Abbott started writing a blog was simple: It seemed like the only viable route he had to being a sports writer.

As the NBA deputy editor for ESPN.com, Abbott will have a different kind of task. Instead of building a new franchise from the ground up, he’ll have to apply lessons from TrueHoop to take ESPN’s NBA coverage in a new direction in order to meet fans needs — and better compete with the future TrueHoops of the world. Abbott’s excited about what comes next, but realistic about the challenges facing everyone in the media business. “All in all, I think the exciting and terrifying part of this is we really can’t do things the way they’ve always been done,” he told me. In our conversation, we talked about how the path to becoming a sports writer has changed, what kind of coverage NBA fans expect, my poor Minnesota Timberwolves, and the rise of sports analytics. Here’s a lightly edited transcript of our conversation Justin Ellis: What do you think NBA fans are looking for in their coverage of the league today? Henry Abbott: I guess I’m in step with everybody in this industry in that I don’t really know. We know it was different than it was in the past, right? But we’re not navigating roads where we can say “Oh, we’ll follow these signs — this is how you achieve success.” What I’m thinking about is we’re navigating by stars. Some of the stars [the audience] want it mobile, they want it fast, they want it accurate, they want it thoughtful, they want it with good storytelling. I think we’re probably too distant from the players. Social media is making it clear players have all this infinite personality, and I think the audience wants it up close. They want to feel the character of the game too. We’re trying to achieve all those things and how that’s best done is a process of experimentation for the next couple decades. Ellis: Contrasting when you started writing and today, there was that whole era where people were questioning whether blogging was a good or a bad thing for journalism. How do you think blogging has changed sports coverage and reporting on the NBA? Abbott: It definitely shook up the snow globe big time, right? It used to be a very small channel of entry to be able to write about basketball all day every day. Basically, you had to know your local newspaper editor and get entrusted with a beat job or covering high school sports. That was just one subset of the population who got to have an audience on basketball. Blogging just let everybody who wanted to try it try it. And that was a subject of concern for a lot of people. I think most of the concern boiled down to “With no barrier to entry, do these people who are doing this have any reason to do this? Should we believe them and are they accurate?” I guess the answer is now all over the place. The blogging that matters to me, that has at the forefront of the TrueHoop network, and that has launched a lot of careers over the last few years, is blogging where people are very scrupulous about being accurate. You can’t shoot from the hip and say, “This guy is a jerk.” You have to make evidence-based decisions. I think blogging has opened the door to everybody, but what’s especially interesting is opening the door to this kind of new, more analytical, evidence-based thinking. Which is interesting and important. At the Sloan Conference, researchers from all over the world know all kinds of bits and pieces of things that totally matter to the game of basketball we’ve all known and loved our whole lives. What package does that go in? Is that a news story? That three-pointers are more valuable than we thought they were? It doesn’t really have that urgency, but it’s massively weighty if you care about basketball. I think blogging has been a conduit for that kind of knowledge, generally. Most people who write about that stuff started blogging. That’s something I appreciate about blogging: the idea of just letting in people. Ellis: The NBA has people who do coverage on the NBA. It has its own network. And at the same time, you have players with their own Twitter accounts who can connect directly with fans. How has the speed of digital media from the league and from players affected the way journalists cover it? Abbott: The rosy answer to that is that it’s harder to lie. There’s so many different people chiming in to call you on it if you do. I wrote for magazines — including the NBA’s official magazine — and I don’t know that we ever heard from anybody about anything. You just wrote what you wrote, did your best. Nowadays everything is reacted to and cross-checked and triple-checked within seconds. You have to think really hard about exactly how you’re gonna break that. I think we’re digging into things with more accuracy, all in all, than before. Which is great. The downside is it’s kinda a mess. It’s just hard to figure out what’s going on minute to minute. Where’s the handy rundown of what matters today? Everything is all over the place and there are so many platforms and channels to keep track of. Ellis: When TrueHoop became a network, what was the benefit of building a network of writers? And looking at it today, how well do you think it worked? Abbott: It solved a lot of problems. One problem was there was a lot of talent in the long tail, as they call it. There are all these really good writers out there who — where are they gonna go, what are they going to do? It seemed nice to affiliate with all these smart, hard-working people. I don’t think anyone was really in a position to be like “Hey, we got jobs for everybody!” But we could offer them some kind of platform and endorsement. These are really earnest, hardworking, truth-telling bloggers. That’s still the reason to keep it going. But I think what we’ve found as it progresses is that the best stuff, we don’t want to have on an affiliated blog — we want to have it on ESPN.com. So all these characters — like Ethan Sherwood Stauss, who’s 100 percent a product of the network, but we elected to give him space on ESPN all the time. And I think that’s been great for us. Ellis: You were an outsider bringing TrueHoop to ESPN, and now you look at someone like Nate Silver, who’s was brought in first at the Times and now into ESPN. What does it say that people who started as outsiders are being brought into these large media companies? Abbott: I think it goes back to what I was saying in the beginning, that there’s not a well-worn path here. I think the ESPN honchos have been pretty wise to recognize that things are going to be different in the future. There are no push-button solutions, but there is this kind of band of oddballs like me who’ve been scouting around the fringes for a while and have some sense of what feels like it might be handy. It’s shifting in a digital way. It’s shifting in a multimedia way. It’s shifting in an evidence-based way. Daryl Morey’s weird stat geek conference is suddenly the epicenter of networking and hobnobbing for NBA jobs. That’s a shift. I just think there are more and more editors, and people in positions of power in publishing who are like, “You know, those guys who have been out there on the web doing this for a while? They know things we want to know.” Ellis: Statistics have gotten smarter and more complex, through things like Player Efficiency Rating or this presentation at Sloan about Expected Possession Value. How do you think this explosion in stats has helped people understand the league? Abbott: For me, it’s not a hobby. For some people, stat geekery as a category is in and of itself fun. I think I’m probably like most readers where I kinda want to get into this. Neurological research these days is so fascinating, because we thought humans worked one way, but now that they do MRIs and learn about hormone secretions and all these things. There’s so many parts of us we leave to vague descriptions from doctors who didn’t really know — to now it’s, “No, this is how your brain operates.” Basketball is working like the brain, where now — you’re describing this research — as the ball moves around the court, we’re going to know the expected points value of that possession, moment to moment. Which suddenly means you gotta pass that ball to the open man right there. Now we’re actually saying the expected points for that possession go from .69 to 1.1 — and that’s how you win a game. Which is what we all want to know. So the fact of the matter is the best knowledge we have is that complex now — or a lot of it is. It’s not categorical, it’s not emphatic, but it’s insightful as heck. I think that’s where a lot of the interesting knowledge is now. When you put on your little detective hat digging for the truth, you end up talking to a lot of Ph.D. students, with their spreadsheets and their SportsVU. Whereas you used to talk to the trainer, I guess? That’s where the insight is right now in a lot of cases, so that’s where we have to go find it. Ellis: One of the things you’ve been doing a lot lately with TrueHoop is TrueHoop TV. How does that add to what TrueHoop is doing and what does it provide to readers Abbott: From the early days of TrueHoop, I felt like I wrote a lot of long, boring, smart things where I was just sure I was right about everything. But the fact is not many people wanted to read that. So I’ve learned a lot from Royce Webb and Chris Ramsay and people here at ESPN about how do you package ideas so they’re more inviting to a general audience. I don’t want to be the expert of experts in some ivory tower somewhere. I want to actually get ideas across to basketball fans. So TrueHoop TV is just way more inviting. I can’t do all the same essay-ish stuff, but you can watch it in five minutes on your phone and it can be insightful. All kinds of people at ESPN have all this knowledge, and I just think short-form original video conversations that are fun and inviting are probably one of the better tools we have to get that across to people. And people seem to like it. Who thought that two oddballs talking from their desks by Skype would ever get 300,000 people to watch it? But that actually happens some times, which is amazing. And encouraging. Ellis: So Twitter. It’s a way to keep updated on stories and follow writers you like, but it also becomes very interesting in real time during a game. Watching something like the All-Star Game, which is always a so-so affair, becomes more interesting when you’re following it on Twitter. What’s your approach to social media? Abbott: I mean, I love it for the eight times a day there’s something I couldn’t have known any other way. I hate that I have to wade through 5 gazillion things to get to those eight. There’s no simple solution there. So you’re a Timberwolves fan. If you’re out with a friend at dinner and coming back from the bathroom you want to know how the Timberwolves game is going, you probably want to know the kind of stuff that’s on Twitter. But you don’t have time to scroll through everything that Twitter has to say about that without delaying your dinner. That’s a riddle to solve, the density problem — how do we get higher density of the best stuff from social media. Ellis: You’ve been moving on this arc, from TrueHoop, to the network, and now this, where it seems like you get further and further away from writing. This might be a silly question, but do you want to have more regular opportunities to do the types of writing you were doing when you started out? Abbott: That was a big decision and a big thing to think about in doing this job. I basically just told myself: Let’s try it. I’m gonna put my head down for a few years and just do this job, and I’ve got so many things I’m excited to do in this job. If at the end of those two years, we figure out that I just miss writing so much, there’s always that. Also, it’s not like I can’t write. It’s just a question of time management. If there’s something I’m just dying to write, I’ll just write it. But I’ll definitely have less time for that. And it’s not really fair to all the great writers here to take time from helping their stuff get the best spotlight it can, where I’m just like “Oh, no, I’m working on my story right now.” I don’t want to compete with Marc Stein for anything. I think I’ll do a lot less of that. I don’t know how much I’ll miss it. I occasionally do find myself on the phone with some other writer here saying, “Hey, you should really write this, but you should write it this way, and you should say this, and say this.” And then I have to stop because I realize what’s actually happening is I’m writing over the phone. We’ll see how much that happens and how much I annoy people. Photo of Justin’s unfortunate Timberwolves playing by Doug Wallick used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

By the middle of 2012,

By the middle of 2012,

That was almost a decade ago. Now the founder of the NBA blog

That was almost a decade ago. Now the founder of the NBA blog