Nieman Journalism Lab |

- FW: FW: Fw: FW: Fwd: fwd: fw: LazyTruth tackles false claims in email chain letters

- Tuesday Q&A: Tumblr editor Jessica Bennett on new platforms for news and the rise of the GIF

- The New York Times’ Chronicle tool explores how language — and journalism — has evolved

| FW: FW: Fw: FW: Fwd: fwd: fw: LazyTruth tackles false claims in email chain letters Posted: 13 Nov 2012 05:35 PM PST

Your Uncle Larry from Pensacola, the one who still has a faded “Impeach Clinton” bumper sticker on his pickup, wants you to know something: Barack Hussein Obama, that socialist we just re-elected, is abolishing the national Christmas tree this year. This isn’t a rumor; this is a fact. And now you have two choices: delete this email or forward it to everyone you know. The Internet’s oldest social network still hums with chain emails like this. FactCheck.org calls it a zombie rumor, returning from the dead every year since Obama took office. The president is a constant target of the email rumor mill: He is a radical Muslim; he canceled the National Day of Prayer; he gave away part of Alaska to Russia; he lets his dog fly on its own jet. We just went through a highly fact-checked election, but it’s unclear what the final score was between truth and fiction. One reason why myths persist is that fact-checking is often out-of-reach at the moment it would be most useful — like the moment where you open your inbox. Forwarding an email is a lot easier than hunting for evidence. So Matt Stempeck, a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab, is tackling the problem closer to its source. Stempeck and developers Justin Nowell, Evan Moore, and David Kim have written a Gmail plugin called LazyTruth that quietly scans your email for chain letters, urban legends, and phishing scams. When you open a forwarded email, an “Ask LazyTruth” button invites you to investigate. The software checks the email against data pulled from PolitiFact and FactCheck.org, and, if needed, offers a correction and a link to find out more. Once a user clears the first (and only) hurdle — installing it as a Chrome extension — the plugin does all the work. The gap between the consumption of misinformation and the correction is reduced to nearly zero. (When it works.) “The Washington Post has a great fact-checking column, but it’s for people who read the Post once a week, dive into a fact-check for 500 words,” Stempeck said. “There’s a much larger audience of people who would want the summary of that in one sentence if they get the email with that lie or mistruth in it. Basically, as far as journalism goes, it’s seeing if we can take the homework and the research and the knowledge that goes into an individual article and bring it out into the world and give it to people when they really want and need it.” Take FactCheck’s fact-check of a chain letter claiming the president secretly criminalized protests against him. The deconstruction of that claim is breathtaking in precision and rigor, but it’s unlikely to reach the people who ought to read it. The people who trust the chain letter in the first place probably want to believe the claims are true. This is the essence of truthiness: “the quality of preferring concepts or facts one wishes to be true, rather than concepts or facts known to be true.” Which gets to another problem: Are the people who install LazyTruth the people who really need it? And shouldn’t LazyTruth be an AOL plugin instead of a Chrome extension? Stempeck said he expects LazyTruth users to be a mostly self-selecting, technically inclined audience. And that does not defeat the purpose, he said. He may not be able to reach Uncle Larry, but maybe he can empower Uncle Larry’s relatives with facts to help bring him back down to earth. “I’ve received emails from friends of my family saying that climate change has nothing to do with mankind,” Stempeck told me. “Off the bat, I know that that’s not true, but I’m not always going to take the time out of my day to go summarize the recent science on it in two quick paragraphs for my friends. If I had a tool that surfaced that for me, I might be more likely to respond with that information.” Stempeck wants to see if LazyTruth inspires people to push back in any number. Would 1 percent of users pushing back make a measurable impact on the spread of those emails? If it sounds similar to Dan Schultz’s Truth Goggles, the work we wrote about last November and again in May, it is. The two have worked together at the Media Lab’s Center for Civic Media. Stempeck hopes to make use of Schultz’s work with natural-language processing to identify variations of common phrases in chain letters. For now, LazyTruth can only match exact strings against Stempeck’s huge and growing database of chain letters and their variations. Chain letters have a lot of common features: They tend to be laced with exclamation points. They tend to be anonymous. They tend to be conservative. They tend to be riddled with spelling errors. And they always insist this is not a hoax!!!!!!!!! To help debunk — and not reinforce — email myths, Stempeck has studied The Debunking Handbook from Australian researchers John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky. “If your content can be expressed visually,” the guide advises, “always opt for a graphic in your debunking.” So for the zombie Christmas tree hoax (Stempeck’s favorite), LazyTruth offers a photograph of First Lady Michelle Obama and Malia Obama in front of the horse-drawn wagon conveying the national Christmas tree, the sign reading “White House Christmas Tree 2010.” Other tips from the handbook:

Next Stempeck wants to mine the data to learn more about the content of chain letters, how they mutate, who the primary actors are. “Some of these emails, they’ll get updated for different nations and context,” Stempeck said. “I would also love to do some network analysis of how these things spread, how many people need to forward them for them to stay alive, and how many people actually forward them versus people that don’t? Is it like spam, where .001 percent is enough to keep it alive?” Please forward this story to 10 people in the next five minutes. Photo by Dave used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Tuesday Q&A: Tumblr editor Jessica Bennett on new platforms for news and the rise of the GIF Posted: 13 Nov 2012 08:30 AM PST

Tumblr is a media company in the same way Facebook and Twitter are — they offer a venue for people, as well as publishers, to share content. But Tumblr, which takes a more bloggy spin on social networking, wants to define itself as a place for editorial products, not just a repository of images from old sitcoms. Earlier this year Tumblr hired Jessica Bennett, a former editor and writer for Newsweek, as its executive editor. Bennett said her days are spent mining Tumblr for ideas and helping to promote all the ways publishers and individual writers are using Tumblr for storytelling. In our conversation we talked about why writers embrace Tumblr, the ways storytelling is being shaped beyond text, and why GIFs — just named the Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year; sorry, YOLO — are ascendant. Below is an edited transcript of our conversation. Justin Ellis: With Hurricane Sandy, Tumblr became a shelter for some of the New York publishing industry. Why did publishers hop on Tumblr when their sites went down? Jessica Bennett: My feeling is, in crisis mode, people aren’t necessarily going to multiple sites to get their news — they’re probably going to one place, whether that’s Twitter or Tumblr. It’s kind of a one-stop shop. There’s obviously a really engaged community on Tumblr already, and we’re heavily populated in the New York area, so I think for sites like Gawker and Jezebel, it kind of was a perfect fit. The simplicity of the Tumblr design they chose fit well with what they do on their blog network anyways. And it’s worked out really well. There was a ton of stuff that was breaking all throughout Tumblr that you wouldn’t have found elsewhere. Ellis: Do you think this was a test case that might push publishers, or anybody really, towards Tumblr as a platform? Bennett: I hope so. Actually, I think most publishers are on Tumblr by now. But certainly in a time like this, when people couldn’t get their news elsewhere, it was a great place to go to. I do love that, in the dashboard on Tumblr, it’s a place you can go to get news where you’re only focused on a single news item at a time. Just by the sheer nature of the design, there’s no pop-ups, you’re not looking at links to other stories, no one’s trying to entice you into another piece. You can actually focus your eyes on one thing at a time. And that’s so rare in today’s oversaturated and constantly bombarded news world. Ellis: It does seem that Tumblr inspires more visual thinking, more of an interest in presentation, than you see elsewhere. Bennett: Even if you have a long-form story, which we’ve seen a big resurgence of on Tumblr in general, choosing the right photo to go with it and choosing where you want your text break to be. The fact of the matter is people don’t want to have to scroll endlessly to get through your post — they want to look at the headline, maybe a few lines of text and the photo, and decide if it’s something they want to click on. I think people think a lot about their display and imagery on Tumblr, almost in a way more so than they would a regular website.

Ellis: It seems like GIFs have exploded, in terms of the election and being used in news. When I see GIFs, I think of Tumblr. What’s been the impact of this explosion on Tumblr? You guys just did a live GIFing event, right? Bennett: It’s been really interesting, because GIFs have existed on Tumblr for some time now, but as Tumblr becomes more mainstream, mainstream news outlets are catching on and realizing that this is actually really fun and can be a really smart way to deliver news and to liveblog. What we did for the elections is we partnered with Livestream and we live GIFed the debates. So we had a team, Tumblr staffers — some of them were people from the community. At Reuters, they were liveblogging the debates; we were live GIFing the debates. We would put all these GIFs out on a site called Gifwich, and then they would be reblogged throughout Tumblr. But more to your point about GIFs and news, somebody said after we live GIFed the debate, that GIFs are like the political cartoons of our generation. I thought that was really smart because it’s true. We use the Internet to express how we feel. We use memes to make points. In the past, people were making cartoons for The New Yorker. Now, maybe, they’re making GIFs on Tumblr. Of course, there are people who will say “can you really have nuance in a GIF?” I don’t think too many GIF makers are taking themselves too seriously. A lot of them are artists. But you can do some really smart stuff by combining actual old fashioned text with a GIF. So we’ve seen a lot of people doing that. People like Ann Friedman, formerly of GOOD Magazine, who has created this whole name for herself by using GIFs to comment on social issues. It’s a kind of fun, interactive way to engage on topics that, yes, are serious. And I think it’s a way to keep people entertained. Even with the binders-full-of-women thing, and more broadly with political memes, that’s the kind of thing that 10 years ago, had Governor Romney said that, I’m sure talking heads all over the world would have commented on it and we would have gotten really sick of hearing them repeat the same thing over and over. But the meme kind of takes on a life of its own and becomes endlessly interesting. There are GIFs that evolve out of it, there are Halloween costumes that were all over my Facebook feed, that have essentially evolved out of this gaffe that turned into a meme. This is probably going way broader than you were asking, but the idea of political memes has really changed the way we cover news and cover politics.

Ellis: These days, it seems that publishers need to make the effort to tailor their message to whatever platform they’re using. It may be one brand, but it lives in different forms in different places. Bennett: Tumblr doesn’t show follower count, and I think that’s led to this culture where people on Tumblr are being judged for the content, rather than who they are. On Twitter, it’s about branding. But a lot of people on Tumblr don’t even use names, or their real names. So you’re really judging them based on the content. When I was doing the Newsweek Tumblr, I don’t think people were following us because we were Newsweek, because on Tumblr it was a bunch of young people who were like, “Oh, wait, Newsweek still exists?” We actually got comments like that. But they liked what we were doing content-wise. So they decided to follow us. And for Newsweek, it kind of opened them up to this whole new audience that they hadn’t reached in probably decades. So I think there’s something to be said about the quality of content, because it’s about what you post, not about who you are or how many followers you have. For news organizations, I think there are really innovative ways you can use Tumblr as a reporting tool. WNYC has done this a bit and Yahoo News did this — where you may have your main story on your site, but then you have overflow. As reporters, how often do we have to cut quotes we spent days, weeks, and months getting that are really important but won’t fit into the space of copy we have allotted? Or just comments that start flooding in from other people’s stories. People have been able to use Tumblr as supplements to their general news coverage. And I think they’ve embraced the idea that content on Tumblr should be different — nobody is going to follow an RSS feed they can get on your website. So people are using it in really interesting ways. Ellis: This relationship between Tumblr and news organizations goes in both directions now. News organizations are finding different uses for Tumblr, but at the same time, you guys are trying to do more editorial things yourselves. What’s your mission in terms of doing editorial for Tumblr? Bennett: A lot of what I try to do is bring the story ideas that are coming out of Tumblr to the masses. We have our site, Storyboard, which is our official editorial arm where we produce feature content every day. But realistically, most of the people who know about Storyboard are already on Tumblr — they’re going to be getting this content regardless.

What I’ve been trying to do is partner with mainstream news outlets, or legacy news outlets, to co-produce, co-publish, or syndicate the content that we’re putting out so we can reach a different audience. It’s easy for us to reach our own audience — we know them, they’re there. We have all sorts of ways of getting to them. But I think the idea is to broaden it so that people who would read a news magazine or listen to NPR would be interested in the stories we are telling. We’ve partnered with WNYC, we’ve partnered with MTV News, the Daily Beast, where we’re bringing the content to both audiences. That’s been really successful for us because it’s this idea that this isn’t about competition for us at Tumblr — we just want to tell good stories and get them out to as many people as possible. If that means sharing out content we’re completely happy to do that. If we’re producing quality content that places like NPR want to run, then great. Ellis: It must be interesting to discover how people are using it and what kind of subcultures are popping up. Bennett: Story generation and idea gathering in my job is so different than any other job I’ve had in traditional journalism. I spend a lot of time just digging through Tumblr — searching tags, talking to other people on staff who might have noticed something I didn’t — to try to tap into what is evolving on Tumblr and the subcultures that do exist. We joke that we’re always trying to find out what the teenagers are doing. But as of now, Tumblr is hard to search. There’s so much going on. Part of the reason we exist as an editorial arm is to help people see what’s actually happening on this platform, because it can be really overwhelming. For example, there’s this huge, huge group of fans of One Direction, the U.K. boy band, within Tumblr. They were all using these really specific tags to talk to each other and create fan fiction and animated GIFs of the boys in the band, to share songs and stories. There were fashion blogs popping up and there was something called “Imagine,” where girls would describe their perfect date with Harry, and then they would actually illustrate it via the outfits that they would wear. So when we were researching a piece on One Direction, we did a feature story — we actually went out to California and produced a video with a bunch of Directioners, which are the super fans, at a couple of shows. And we produced a guide to fandom within Tumblr. I spent hours and days tracking this tag in the Tumblrsphere, and it moved so quickly that I could barely keep up with it. Nobody really knew of its existence other than the fans themselves. When the piece came out, we got tons of death threats by Directioners, who thought that we had broken into this secret world that they had, that they didn’t think any grownups were allowed into, essentially. It was just really interesting to see. You’re on a public website, you’re using the web to document everything you feel, and it’s all about sharing. Yet, these teenagers felt this was still a private community for them. And that exists again and again and again. There’s so many fan cultures on Tumblr. You can create these micro-communities, and the challenge for me is finding the micro-communities. |

| The New York Times’ Chronicle tool explores how language — and journalism — has evolved Posted: 13 Nov 2012 07:30 AM PST

It’s possible The New York Times is using the word “signature” too much. I’ll let Philip Corbett, the paper’s standards editor, explain:

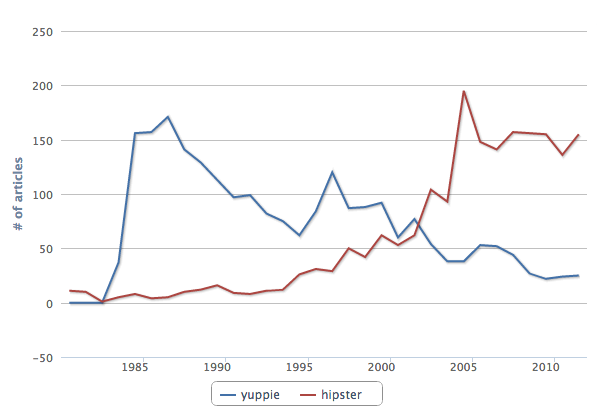

As the guy in charge of standards, Corbett has to have a keen eye for detail on what appears in the Times every day. But how widespread is this, er, signature problem? Thanks to a new (internal, alas) tool from the New York Times Co.’s R&D Lab, we have the data to know for sure. (Since 1981, usage of “signature” has increased at the paper, peaking in 2010 when the word appeared in more than 1,500 articles.) Chronicle is a database of articles and story tags from the past 31 years of Times content. The tool makes it possible to see the frequency of use of certain words — but also what people, organizations, or locations are most related to keywords. “It’s a way of being able to see patterns in our vocabulary — not just in topics in the news, but in language and how we talk about the news,” said Alexis Lloyd, a creative technologist in the R&D Lab. For instance, using Chronicle, you’ll find that the word “terrorism” was used as a tag in more than 7,000 articles in 2004. We can also see that among the most related tags to terrorism were, to no one’s surprise, George W. Bush, Saddam Hussein, and Al Qaeda. Chronicle also lets you chart how words have risen and fallen over time by the number of Times articles they have appeared in. The comparison tool, for example, shows that the word “yuppie” has been in decline since the mid 1980s, while “hipster” has shot upward. “We almost stopped using the word ‘decor’ in 2001,” she said. “[Usage] went up and up and up and stopped. There was an editorial decision that was made.”

Word choice can be an agonizing but prideful task for reporters. While certain words are necessary for conveying the facts of a story, others allow for a signature touch. But Chronicle wasn’t meant to be used as an adjective monitor. Michael Zimbalist, vice president of R&D for NYT Co., said the paper is trying to find new ways to put its index of articles and taxonomy of story tags to better use. What the Times is sitting on is a mountain of semantic data that opens up many research opportunities, Zimbalist said. “We’re looking at a giant corpus of text we have here and how to process that text as data,” he said. Chronicle is similar in many ways to Google’s Ngram Viewer, which lets users compare phrases that have been digitized in conjunction with the Google Books project. Both projects seek to learn more about the ways language has morphed as cultures have changed. A newspaper represents a constrained body of work to study, Lloyd said, because stories are largely based on current events, but also because newsrooms are subject to regularly updated style guides. “This gives you a particular view into news and culture and history,” she said. Though the Times has an extensive archive and a rich system of metadata, Chronicle’s data only runs 31 years back — to the 1981 start of the paper’s database of full-text articles. Lloyd said her next challenge is finding a way to extend the corpus deeper into the Times archive. At the moment, Chronicle is in the “not for public use” part of the Times R&D Lab. While the search tool has potential uses for research, Lloyd said she wants to focus on expanding the corpus to make the results richer. At the moment, Chronicle will only be available inside the walls of the Times. “I think it can be used for research and reporting,” Lloyd said. “The primary idea is to have it as an internal tool to be able to get those aggregate views and look into trends and patterns you can’t get at any other way.” |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The fall of 2012 should leave no doubt that

The fall of 2012 should leave no doubt that