Nieman Journalism Lab |

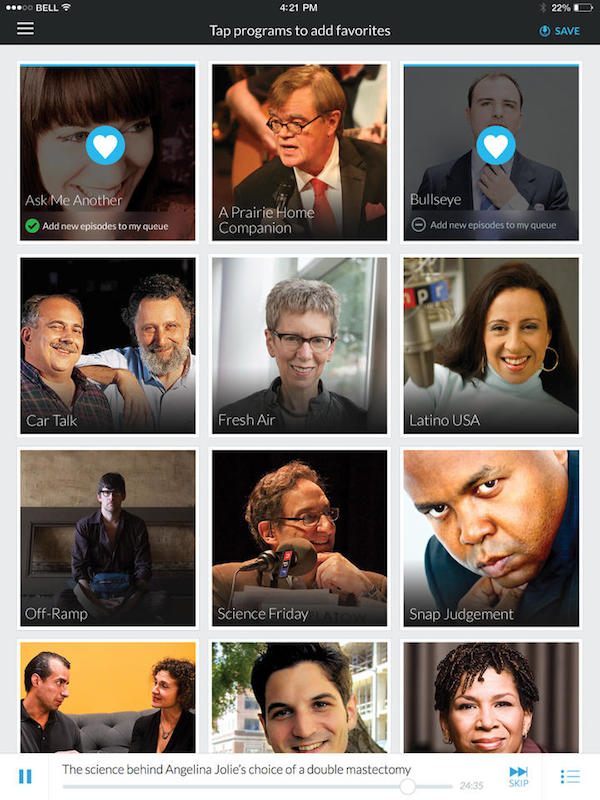

| The newsonomics of public radio’s all-in-one tablet strategy Posted: 12 Dec 2013 10:56 AM PST It’s a tablet experiment in cross-pollination. How do you use the 48 square inches of an iPad to expose the depth of public radio — thousands of hours of national programming, local shows, and community news that add up to a window on the world? In southern California, KPCC’s new iPad app is a shape-shifting kind of product, heralding a new local promise — and offering an insight into what a greater shared local/national public radio experience may look like. All the metaphors in the product may not perfectly jell — it is a newly released V1 product — but its ambitions are great. It is only the second local public radio iPad-specific news app in the market (Minnesota Public Radio’s launched earlier this year) and acts on the realization that more than half of public radio’s digital traffic will likely be mobile by 2015. Indeed, in a world where radio is still valued but a radio is becoming an anachronism, the new app acts on our near-compulsion to toggle. What strikes me about the KPCC app is its largely successful attempt to bridge different elements that could otherwise be in tension with one another. First and most importantly, it’s local news and it’s radio programs — a balance many public radio sites find hard to strike. On the news side, it’s both locally curated twice daily and it’s a stream of news. It’s local news and it’s national news. It’s text news and video news and audio news. On the radio/programming side, it’s radio and it’s audio. It’s livestreaming and it’s on-demand programming. It’s whole programs and it’s segments of programs. It’s an exercise in toggling. We’re well beyond the old binary controls of balance, bass and treble. It’s a consumer movement across content types and brands: Media can no longer choreograph it — they can only provide a suitable stage. The bridges here are important because of all that complexity. Just as important is the role of personality. It’s inarguable that we take in the human news voice differently than we do the written word. Public radio leverages this personality — resulting in a mass medium that has grown in usage and reach markedly over the last decade — and does it uniquely. There are lots of public radio apps, but almost all of them rely on words to stand for a program. The KPCC’s “All Programs” page is a set of photos of program hosts, from Fresh Air’s Terri Gross to Marketplace’s Kai Ryssdal to KPCC’s Larry Mantle. Touch the picture, and you get to current and most recent episodes. Want to use the app as a “radio”? Just edit your favorites and then new shows are automatically added to your queue.

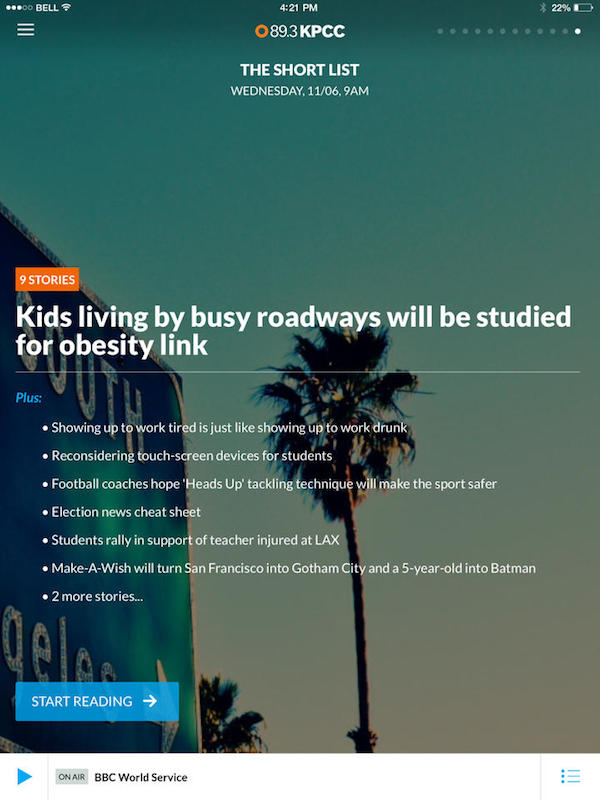

The central idea of the design: Make it easy for readers to move back and forth between and among these various content types. That means a live listening bar available on the bottom of each page, and a number of ways to get back to news or a program with a single tap. KPCC’s Alex Schaffert is a digital veteran, having spent eight years at the station, and as director of digital media headed up the project. The effort is funded with a $1 million, two-year grant from the L.A.-based Keck Foundation, paying for some outside conceptual design help and five full-time positions. Schaffert emphasizes that given the fundamental shift in the business to mobile, developing internal expertise is now a given. “The KPCC iPad app was entirely built in-house,” she says. “Many news organizations outsource app development, but I think we’ve reached a critical juncture where the user experience, the design, and presentation of news are just as important for a winning product as the content itself. App development shouldn’t be an afterthought, delegated to a vendor. The presentation of news in the mobile space is core to our business today, and in my opinion it’s vital that news organizations build that expertise among their ranks. You need programmers working side-by-side with product people and content producers in order to arrive at an innovative product.” Like most big public radio stations, KPCC has seen explosive mobile growth, with mobile now at about 35 percent of digital traffic. Its smartphone app has been useful, but the station wanted to seize the platform of the day, the tablet, and use it as a base for KPCC’s large local news ambitions (“The newsonomics of the death and life of California news”). Those ambitions have grown, as former L.A. Times editor Russ Stanton and former Sacramento Bee editor Melanie Sill were hired as VP/content and executive editor, respectively. The news staff will number 100 by the middle of next year, as the print landscape in the Southland swirls with post-bankruptcy intrigue, consolidation, and more news capacity shrinkage than expansion. In looking at data, KPCC found that its audience is even more iPad-centric than the population overall. It’s a strong two-year trend line; even with KPCC’s smartphone apps, iOS downloads outdistance Android nine-to-one. In addition, there isn’t much overlap between radio listenership and digital use at public radio stations nationwide. Fewer than 20 percent of listeners regularly use a local station’s website or mobile app; fewer than 20 percent of its app or website users listen much to its radio offerings. That understanding opened up design as a green field to attract new audiences. Behind the design are those five staffers. One manages the product, two are developers and the other two produce the app’s centerpiece, The Short List, a highly visual feature. “It’s a need-to-know product,” says Schaffert, interestingly using the same words New York Times CEO Mark Thompson uses to describe one of his planned new paid digital products. The idea: 10 stories, picked early in the morning for the peak 8-9 a.m. mobile reading hour and then again in time for the 4-5 p.m. surge. They are drawn from local (KPCC) and national (NPR and AP) reporting, from big global news (“India’s Supreme Court upholds anti-gay sex law”) to the occasional large reptile story (“Did the dinosaur asteroid send life-bearing rocks to Mars?”).

We toss around words like multi-platform, multi-device, multi-screen, and “news everywhere” to describe the countless choices consumers have. From a publishing point of view, though, these choices have created headaches, posing tech and cost challenges — even before we get to the over-thought existential ones. As a radio station, KPCC is grappling with the same existential issues as other legacy media trying to break beyond their legacy platforms. With Rebecca Howard’s new charge at the New York Times, we see the same effort, as we do in Cincinnati (“The newsonomics of Scripps’ TV paywall and the Last Man Standing Theory of local media”) and many other markets, as local TV stations go digital and text. How do you show both who you are and who you aspire to be? The solution: Put aside vain attempts at self-identification (and self-esteem) and imagine yourself behind the customer’s eyes and ears. That’s what the BuzzFeeds, Circas, Der Correspondents, and all the other digital startups do. The world provides us with a simple truth: We consumers have proven to care little about Old World definitional differences. We simply like what works. Where might this product go? If it’s static, readers may write it off as a good start, but one not satisfying enough for the deep-reading public news audience. If it develops, though, in breadth, depth, and navigation, it could offer up new ways to deepen relationships with members (who contribute 53 percent of the station’s revenues; full station report here) and introduce new customers to public media. Further, KPCC’s new platform, along with other recent innovators — including New York’s WNYC, which recently produced a state-of-the-art audio-centric smartphone app — could well take advantage of a long-in-discussion wider public media network experience. Despite all the change at the top at NPR (seven “permanent” or temp CEOs in six years), NPR has continued its talk with top public radio stations in major markets around the idea of what once was called “Pandora for public radio,” as a number of top public radio execs have shared. That idea is as “simple” as KPCC trying to make consumer simplicity out of its welter of radio/audio/text offerings. In fact, the national complexity is far greater, given the multiplicity of news staffs, personalities, technologies and market strategies found around the public radio country. Those are just the organizational questions; how these products will generate substantial revenues is still to be determined. Though the national NPR is fundamentally different than the regional KQEDs, WBURs, OPBs and WBEZs, it’s a meaningful difference that isn’t meaningful to consumers. Add in public radio power centers like CPB, APM, PRI, PRX, and other funders, creators and producers of programming, and the ability to balance priorities, revenue streams and traffic flow can seem practically Rubik’s Cube-like. Still, expect NPR to get to a harmonic convergence far sooner than later. Already, much smart work has been done at mastering the content management to allow greater sharing and use of content among public radio stations and NPR. Now it is the business issues that must be finally wrestled to the ground, as national/local relationships inevitably must twist and turn in the next mobile age. If all that messy sausage-making can be resolved, then public media could do on a national/local level what KPCC is starting out to do in L.A.: Make it finger-simple to move in and play among the bounty of public media content floating through the country on any given day in words, voices, music, pictures, video — and the personalities animating them. For public media, it’s not just a question of upside, though there’s plenty of that which increased engagement can generate in dollars. In every news and entertainment medium, it is the aggregators — the Googles, Facebooks, Netflixes, iTunes, Hulus, Spotifys, Pandoras and Flipboards — that show the greatest growth. (And in each of those industries, we’ve seen fierce controversies about publisher/creator role in aggregation, controversies that usually last long enough for the incumbents to forever lose their standing.) Against that landscape, public media still possesses the ability to pull itself together. At the same time, there’s a deepening appreciation that if it doesn’t pull itself together soon (and even if it does) the TuneIns, iHeartRadios and Stitchers may well succeed in creating audio aggregations to beat all other audio aggregations. For public radio, smart, teamed curation with the consumer utmost in mind is only the first step in meeting that emerging competition, and deciding where to compete and where to partner. |

| Q&A: Sarah Marshall on leaving Journalism.co.uk for the WSJ and the state of media across the pond Posted: 12 Dec 2013 06:30 AM PST For three years, Sarah Marshall has held a job that’s pretty similar to, well, my job. And I think she’s pretty good at it! But Marshall is moving on, from Journalism.co.uk, the 15-year-old journalism news site based in the U.K., to The Wall Street Journal, where she’ll be the inaugural social media editor for news coming out of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Marshall worked in print media before coming to Journalism.co.uk as a reporter. She’s also one of the Hacks/Hackers London organizers, part of a dream team that includes Joanna Geary and Cassie Werber. (Marshall says they do let some men get involved, sometimes.) Marshall only started at the Journal on Monday, but after three years covering the media business, Marshall has a lot of insight on the future of journalism, both globally and in the U.K. That experience allows her to point out topics we might talk about a bit too much — like drone journalism and the eternal learning-to-code debate — and those that don’t get enough attention — like news as a service and geotargeting. Marshall and I chatted about these subjects and more over the phone; an edited transcript of that conversation is below. Caroline O’Donovan: What kind of stories were your favorite stories to work on? Did you have any pet subjects you thought were especially interesting? Sarah Marshall: It’s always the innovation. I’d been at Journalism.co.uk for almost three years. The amazing thing is in three years, a lot happens, a lot changes, but I guess the things that really make your ears prick up or your eyes open more widely when you see something on Twitter is the innovative stuff. Things like people using analytics in different ways. It’s quite an old example, but Homicide Watch, finding stories by using that technology that we all think of for monitoring. I love the robot reporting stuff that the L.A. Times does, for example. O’Donovan: You know, it’s funny — I don’t think I’ve ever come quite this close to interviewing someone who is basically doing the same job as me. Marshall: It’s funny, isn’t it? O’Donovan: So, you said, robot reporting at the L.A. Times — are you a fan of drone journalism stories, too? Marshall: I must admit, for the past three years, I’ve been seeing drone journalism come up, and, you know, there are certain stories where I think, yeah, it’s kind of an interesting debate. But at the same time, there are more interesting debates to have. Yes, of course, that we now have the technology that means you can put something in the air for ten minutes, that’s kind of interesting for a flood story. But let’s not spend three or five hours at a conference discussing it. Realistically, they’re never going to replace helicopters, because you can’t put them over crowds and things like that. So I think certain things in the industry get talked about kind of a lot when actually, perhaps they don’t warrant quite as many pixels. O’Donovan: You also mentioned analytics. I’ve enjoyed the work of people like Brian Abelson, one of the outgoing Knight-Mozilla Fellows, talking about the pageview as not a super useful number. And then also talking to people like Tony Haile of Chartbeat about building up new kinds of analytics. What’s been the most interesting for you in thinking about that stuff? Marshall: I think thinking about it is when you actually start caring less about metrics. When you don’t do stuff for the sake of pageviews — for example, at Journalism.co.uk, we soon realized that actually we weren’t going to make any more or less money by having numbers. I’m hoping that one of the things in the future that happens is we’re less wedded to metrics, less devoted to pageviews — we’re just devoted to creating good stuff through having strong brands that then pays for itself. That will mean that we don’t do things like chase clicks. One of the innovations, a U.S. example, that I’ve really liked in the last year or so is Evening Edition. The idea that if you send the stories by email, and you don’t expect people to click through if you’re on a weak 3G connection, then you don’t necessarily want to click through to another page — it’s interrupting the reading experience. Also, all of that stuff Anthony De Rosa wrote about on Medium, this idea of why we’re all rewriting 500-word stories that other news organizations already have. If we can divorce ourselves — not totally — from this “how many unique users have we got a month,” then I think the news industry can be a lot more creative. O’Donovan: Which kind of goes, in its own way, hand in hand with the conversations about viral content creation the web’s been having this week. I know BuzzFeed recently made its way to London; I don’t know if public perception of it is the same over there as it is here. (To be honest, sometimes I don’t even know if I know what the public perception of BuzzFeed is here.) But is that a big part of the conversation for you guys? Marshall: I think they’re such an interesting case study. BuzzFeed has become the most Facebook’d news organization this year. This side of the Atlantic, too — they’ve got such a growing team in London. I’ve got friends who work there, and there was a stage when I think not everybody could be in the office at the same time. Within a year of their launch, they had to move newsrooms. There’s another interesting project here, UsVsTh3m, which came out of one of the regional news groups, plus they have a national daily tabloid. They’re creating this shareable content that, you can argue whether or not it’s news, but it certainly gets a lot of clicks. O’Donovan: Do you feel like things like UsVsTh3m get enough attention over here? Or does it not matter, since it is primarily for a non-American audience? Marshall: It’s very, very British. They do this thing called toys, like interactives. I think it was 3.6 million uniques and more shares than Snow Fall on both Facebook and on Twitter. It was a silly thing, this obsession that us Brits have with the north-south divide. It was just a little interactive that took them a day and a half to build. O’Donovan: It’s funny: I’m from New Jersey and we believe that there’s a big difference between northern New Jersey and southern New Jersey, but nobody else in America knows or cares what you’re talking about. Marshall: Yeah, this stuff is not going to travel, basically. But it was 1 million Facebook shares, which is a huge number for this organization that didn’t exist a few months ago. O’Donovan: One thing that has made its way across the Atlantic and seems to have made that transition pretty well is The Guardian. What do you think about The Guardian’s U.S. expansion? Marshall: I think it’s very exciting — I’ve obviously been watching it closely for along time. I think from two months ago, it’s got more U.S. readers than U.K. readers, which is quite impressive when you think about it. From reading various people, you kind of get the impression that The Guardian got it with digital quite early. They created shorter posts that were perhaps easier to consume than some of the perhaps loftier titles. So they’ve done really well. Australia’s going well for them. It’s very exciting to see the number of British news organizations that make it internationally. Whether you love or hate the content of the Daily Mail, the stats are absolutely incredible. O’Donovan: I did want to talk about data journalism. You said Trinity Mirror is doing interesting stuff — what are they up to? Marshall: So they have got this amazing reporter, who’s been slogging away and probably spend evenings on her own going through spreadsheets and scraping stuff, called Claire Miller. She’s been doing great stuff. They’ve now got a little team together and my understanding is they’ve now got that centralized in a hub so nationally they can make the most of that as a resource. O’Donovan: Obviously video is a big deal too. Who do you think is doing it well? Marshall: I think there was a bit of a rush with video. You know, suddenly, if people will watch our news content from their iPads or TVs, they were starting to think: We’re going to get bigger dollars related to TV than newspapers. I think a lot of people did loads of video and then, the stuff that’s worked, of course, is this great content, the stuff that’s really helpful to people. WorldStream is a great example where you’re getting that behind-the-scenes glimpse into the reporter’s life and the bit of extra context, whether that’s breaking news or the behind the scenes stuff. For example, BBC News on Instagram started clipping the content they had into 15-second video clips. You’d think you can’t tell much of a news story in 15 seconds, but actually you can give the sense of the scale of a disaster or do a bit of scene setting. So that’s quite interesting. And then, Channel 4 News here, they’ve created these really nice two-minute videos adding context. They did one about al-Shabaab for the Kenya terrorist attack, with the reporter explaining who al-Shabaab is. There was another one where Lindsey Hilsum was saying there’s a video explaining why we should care about Qatar’s new ruler. Explaining that in a one- or two-minute video, that doesn’t just have a life cycle of today — it’s got a life cycle beyond that. Of course, there’s been lots of other stuff, and video doesn’t have to be short form — Vice is a great case study there. O’Donovan: Two questions about mobile video stuff. I feel like a lot of the people I talk to who are thinking about news in the mobile space are afraid that if they do video, this vision they have of this person who’s waiting for the bus — that’s when we check news on our phones! waiting for the bus! — and that person won’t watch a video in public. They’re worried that reduces the reach of video on mobile. And two, do you think people can adjust or will adjust to using platforms they’re not used to getting news on, like Instagram, for news? Marshall: So, the first question — I actually do think people watch video on the go. I think now, with the connection speeds, you’re able to do it. Once you’re on the bus, you have time to kill. And actually — we all do this — we all use our mobile phone at home. I’ve got a tablet and a desktop and a laptop, but actually, generally, I’m using my mobile phone most of the time to consume news. So I do believe video is perfectly suited to the mobile phone. O’Donovan: And do you think people can adjust to something like Instagram where they’re used to seeing their friends out to eat or in bars — suddenly adding news to that information flow? Marshall: I think that works because people have a choice of whether they follow BBC News or Time magazine on Instagram — they selected to do that. It’s no different from Facebook. In any environment, it’s a real opportunity for news organizations to engage with younger audiences. Think of the BBC, putting themselves on Instagram. Maybe, internationally, that’s the first time a 15-year-old comes across BBC News content. O’Donovan: Are there any major changes or shifts in the British media environment that are significantly different than what we see in the U.S.? I also imagine you have more of a window into what’s going on in the rest of Europe — who might be doing interesting things that we don’t always check in with. Marshall: I think some of the things that spring to mind are the collaborative projects — being aware of the investment in technology. I suddenly get the feeling that Guardian Labs is a “thing”; that, for example, the Irish Times have been incubating some startups in a way that is very much like a competition and have been supporting startups in Dublin. One of the things I don’t think we do as well as the U.S. — and there are a few examples, I’m thinking about Circa and Breaking News — is having mobile-only products. I know they’re not, but I do follow them both on my phone and I think: Wow, they’re a bit U.S.-centric. That we haven’t really got in the U.K. yet, to my knowledge. O’Donovan: What about native ads and sponsored content? How are they perceived in the U.K.? Do journalists there have the same sort of general distaste for it, and do marketers there have the same desire for it? Marshall: I guess I don’t know exactly what most journalists think. I think there’s a ton of excitement. If it helps us stop caring about absolute pageviews — if you can run a successful campaign for a brand, maybe it’s not all about the overall monthly uniques — to me, as a journalist, that’s a real exciting point about native advertising. Of course, there’s loads of people trying it. I know the Journal is doing it, The Guardian is doing it, the Financial Times is trying to work out different ideas there. Loads of people are seeing what they can do in the area. I don’t have anything against that. As a journalist, I think it’s only positive if it helps make digital journalism pay. I am perhaps surprised that it took us so long to realize this was a “thing” — but then, I guess it’s been done in different forms over time. I think as long as you have a different team of journalists — you have newsroom journalists and those people never write sponsored content — I think it is actually quite a happy marriage. O’Donovan: Where do you fall on the should-journalists-learn-to-code thing? Marshall: Again, it’s a bit like drones. O’Donovan: I assume you don’t mean turning journalism students into drones. Marshall: No! If you’re a journalist, and you have to go through loads of council documents, or whatever it is, and you learn you can do that by writing a scraper, you’re going to learn to do that. If you don’t need to do that, you’re not. We have a lot of talk about it, but probably the best — my favorite — reaction to that was Martin Belam who tweeted at some stage, SHOULD BEES LEARN TO CODE? That kind of sums it up all completely; some people will realize that it’s really useful for doing particular things, but I don’t think it warrants all the time we spend talking about it. But there are some — there’s a course at City University called the Interhacktives, and they’re producing some brilliant journalists with some skills that are going straight into national newsrooms and doing data journalism stuff. They stand out. O’Donovan: Tell me a little bit about your job at the Journal. What led you to decide that that was both the position for you in terms of social media and the institution you wanted to be a part of, at least for now? Marshall: I’ve been in this completely privileged position for three years, where I’ve gone to conferences pretty much two, three times a week. I’ve been to conferences nationally and internationally and spoken at several. You get a real sense of which are the organizations that are doing this great stuff. The Wall Street Journal I’ve always followed, and then suddenly I see them making some key hires in social. You start to look at these things — like you, I reported on WorldStream. I noticed the Obamacare video that Neal Mann was involved in. More recently, about the time I accepted the job, Borderlands came out, which was this incredible interactive about normal people about Syrian refugees living on the Turkish border. And then there was this amazing thing they just did on Golden Dawn in Greece. This visual storytelling, I just wanted to be part of it, and once I heard the job was coming up, I was dead keen. O’Donovan: So what kind of stuff are you going to be doing? Do you have a sense of that? Marshall: So, it’s quite a big area. It’s EMEA — Europe, Middle East, and Africa. I don’t know whether the people in the U.S. have the sense of the size of the scale of the Journal, but it’s 450 journalists in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, including the newswires. It’s a big team. At the moment, there hasn’t been a social media editor. There are four or five in the U.S., Maya in Asia, and until now Europe, Middle East and Africa haven’t had a social media person. It’s not exactly a clean slate — they’ve been doing Twitter and Facebook — but it’s quite exciting to come in as the first person doing that. They’re really ready for it. There are some individual journalists who are really great on social, and this will mean we can bring them all together and highlight those people, and really, hopefully think about how people share content and what people are sharing. It’s very exciting to be doing it as a new role. O’Donovan: Are there any platforms you’re excited to experiment with? Marshall: Quite early on, when Pinterest was still invite-only, I wanted to do a story: Which news outlets are innovating on Pinterest? The one that was doing the most impressive stuff was The Wall Street Journal, funnily enough. I remember thinking, is this really a visual brand? But they created this “How to Use Pinterest” board introducing people to it. I’d really like to crack LinkedIn, I must admit. It’s huge — I don’t think any news organizations have really cracked it yet. I’m guessing it’s a real sweet spot for traditional Journal readers. So I’d love to cracked LinkedIn. O’Donovan: Okay, one more question to wrap up. Is there any big story you didn’t get to cover at Journalism.co.uk? Something that would be on the forefront of your mind if you were staying? And if not, what do you think are the big things your former colleagues are going to tackle in the next six months to a year? Marshall: I hope — because it will help me — I think it will be about the way that smarter technology can help journalists. I think newsrooms are getting the fact that they’re building their own technology — and journalists who have the experience of what newsrooms need, they’re also doing that. I think it will be the technology that helps us all. I’m hoping we’ll see some new products that make you go, Huh! I didn’t know you could auto-populate Twitter lists by theme! Those are the kind of things that excite me. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |