Nieman Journalism Lab |

- The newsonomics of Scripps’ TV paywall and the Last Man Standing Theory of local media

- Where in the world is BuzzFeed? Building foreign news around themes rather than geography

- Freedom of the Press Foundation wants to help build secure communication tools for journalists

| The newsonomics of Scripps’ TV paywall and the Last Man Standing Theory of local media Posted: 05 Dec 2013 07:30 AM PST How much would you pay for online access to Ron Burgundy — or at least the Ron Burgundys of Cincinnati? In an industry-shaking move, E.W. Scripps’ WCPO.TV — that’s the website of Cincinnati’s ABC affiliate — is putting up a paywall Jan. 1. While it may not quite be the first TV broadcaster in the U.S. with paid digital access, it is the first to announce the move. With another station, a Press+ client, preparing to go paywall before the end of the month, this mini-revolution in local TV news may be starting small, but its ramifications could be profound: Local TV news — itself facing a transitional struggle because of digital disruption — is re-orienting itself for a battle with local newspaper news — and therein will lie lots of drama over the next few years. It was the news of a TV paywall — a hard paywall at that — that caught a few headlines two weeks ago when the news broke. But that isn’t even the most intriguing thing about the WCPO push. Scripps is investing in content and in engagement in Cincinnati. In total, 30 people are being hired, “the vast majority” of them in editorial, with multimedia producers, community-oriented staff, and digital sales people filling out that number. How big an investment is that? WCPO, in the 34th largest U.S. market, started out with a newsroom of about 75. Adding more than 20 new people to focus on digital is a substantial increase. "That incremental staff produces content for the digital platforms, but when a reporter breaks a story exclusively (which is happening almost every day) that information/coverage/story makes its way to on-air, though it might be written or wrapped in a different way, appropriate for that medium," says Adam Symson, Scripps' chief digital office. "Our digital reporters often end up interviewed on set as part of the tell. Bottom line, they aren't producing TV stories because they aren't broadcast journalists, but expansion of coverage as a result of the strategy is absolutely positively impacting the depth and breadth of our on-air product every day." What’s behind Scripps’ contrarian play, in an age of news cautiousness? “It’s about winning digital,” Symson says. “At the end of the day, there is room for one, two, or maybe three local dominant media brands. Winning the digital consumer will be the price of admission to being one of those winning brands.” “Winning” is the optimistic spin on that strategy. The flip side to ponder: There just won’t be enough advertising and subscription revenue to sustain any more than one to three significantly sized news staffs in many metro areas. Call this the Last Man Standing Theory of local media. It’s painful to think about, but the last half-decade seems to have born it out year after down year. What’s the business strategy behind the investment? It’s not just about new subscription revenue. Thinking about the numbers, it can’t be. As a free TV station — TV wants to be free, right? — WCPO, unlike newspapers, has no legacy base of subscribers who can be upsold to all-access, digital + print subscriptions. Aggressive all-access pricing is what is behind most of the new half billion dollars in circulation revenue we’ve seen in the U.S.; broadcast can only dream about that. While The New York Times has built up a business on 727,000 digital-only subscribers (“The newsonomics of The New York Times’ Paywalls 2.0″), the top regional dailies are topping out under 50,000 for digital-only subscriptions; most newspapers struggle mightily to see five figures. So what might WCPO, without an existing paying audience, expect? Let’s say it got 1 percent of its 400,000 monthly unique visitors to pay up. That would amount to about 4,000 paying customers. Let’s say they pay $100 a year, on average. That’s $400,000. Or, let’s say 3 percent, or 12,000 — a highly optimistic number, I’d have to say, given the habits here. That would be $1.2 million. Five percent, or 20,000, would bring in $2 million a year. Compare that revenue to the $3 million or so in new costs of the WPCO expansion. Paywall revenue may not be the main play here. Consider two other kinds of revenue the initiative hopes to goose:

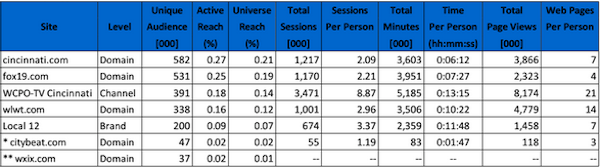

So, the revenue strategy here is three-fold: more digital ads, higher TV ratings, and paywall revenue. We’d have to think this is a long-term strategy; Scripps execs like to talk about the company’s innovative roots and point with pride to the WCPO push as the latest example of it. The WCPO test will likely not pay for itself within 18 to 24 months — but as a long-term investment, it could pay off, especially if the Last Man Standing Theory is true. If Scripps stays the course, and maybe continues to expand WCPO over time — and Gannett continues to chisel away at the city’s remaining daily, The Enquirer — how will the two compare in audience and in digital revenue in, say, 2017? We can ask versions of that same question in many metro areas. What if broadcast builds digital slowly, and print continues to fade away? Or, to frame it a different way: If you’re a company that owns both newspapers and TV stations, which seems better suited to be a base for the mainly digital age to come? Scripps seems to believe it is TV. Why? The legacy costs are smaller; while TV production has its own old-world cost structure, it doesn’t compare to the Big Iron costs of presses, plants, and trucks required for print. And while print ad losses have made newspaper revenue growth largely a pipe dream since 2006, broadcast keeps managing to sustain itself. Odd-numbered years (non-election, non-Olympics) are always lower than even-numbered ones, and 2013 is no exception. So even with massive consolidation in the broadcast industry this year (Sinclair buying Allbritton, Tribune buying Local TV, Gannett buying Belo, among others), TV’s prospects are arguably more manageable than print’s. That realization can be seen in Scripps’ own share price. It’s up 95 percent year over year, largely on the basis of its broadcast fortunes — which now supply the great majority of the company’s profits, though just a little more than half its revenues. That increase is surpassed only by Lee among publicly owned “newspaper” companies. The Cincinnati Enquirer, which pushed Scripps’ own Cincinnati Post into oblivion in 2007, is, like most Gannett papers, cutting back, not adding to its content creation. August layoffs further reduced its staff, as bureaus were reduced, critics packed up their notebooks, and reporters were laid off. Gannett, like most owners of dailies, is retrenching to maintain profitability, as print advertising loss can only be evened out by increased subscriber pricing and cost cutting. Dailies, which had come to think of themselves as monopoly dailies, may be the only big print game left in Cincinnati and cities throughout the country. Those cities, though, often sport three to a half-dozen TV news outlets. What if one of those outlets decided to compete — digitally — with the local paper? That’s one of the big questions we’ll see answered as the battle moves forward in Cincinnati. Already, a top broadcaster may lead the local daily in a quarter to a third of the U.S.’ top 50 markets. If broadcasters invest while newspaper companies disinvest, how much and how quickly could those numbers flip? Check out the latest (October) Nielsen numbers for a sense of the competitive urgency in the Cincinnati market. While Gannett’s Cincinnati.com (which barely whispers the word “Enquirer” on its homepage) pulls in the most unique visitors, at 582,000 to Fox19′s 531,000 and WCPO’s 391,000, the engagement numbers already tell a different story. WCPO averages 13 minutes per visitor per month, more than double Cincinnati.com’s 6 minutes and a little less than twice Fox19′s. In the important engagement metrics, from total minutes to sessions per person to web pages per person, WCPO is a clear leader.

Now, with a paywall and its attendant marketing only weeks away, how will those numbers change? Since most of the new editorial staff has already been hired (10 jobs now open), the results of Scripps’ content investment have already borne fruit in traffic. Consequently, it’s hard to know how much more upside the company will gain. Conversely, the nature of WCPO’s hard paywall could drive down engagement. Sure, lots of content — the kind of relatively commoditized breaking news, weather, traffic, and sports that are staples of TV news — will still be free. And yes, WCPO’s Ron Burgundys should still be largely accessible for free. But readers will run into the hard paywall when they try to read the only-on-WCPO stories, the kinds of stories for which Adam Symson’s research shows a hunger. Stories on education, religion, or health — you know, the kinds of stories that newspapers have long been known for. The new staff hired will focus much on that non-traditional TV coverage. Scripps may be grafting a newspaper model on a digital TV platform. If it is, is that old-fashioned or a brilliant streak of genius? It’s a mind-bending set of media metaphors in search of the digital future. WCPO is going with a hard paywall rather than a meter. It’s closer to many European “plus” paywall models, especially those popular at tabloid newspapers. Those papers, like local TV news, believe that when offering much of the same news as their competitors, it’s better to keep that stuff free and segregate the proprietary stuff. While the meter is all the rage among U.S. newspapers, 2014 will tell us a lot about the success of these plus models in Europe and, maybe, newly in the U.S. In the meantime, WCPO will see how much the paywall limits the crucial sampling of digital content, key both to maintaining high digital traffic and improving subscription conversion. Scripps uses Digital Paymeter, developed by Synchronex and NewsCycle Solutions (formerly DTI) to power both its TV and newspaper sites; the newspaper sites use a meter, though one that is time-, rather than article-, based. Think of the WCPO test in part as R&D for the rest of the company. “Scripps is not a holding company,” says Symson. “It is a consumer products business. You’ve got to get the the product right first.” If it gets that product right — along with the paywall model and the pricing (which is still TBA, but likely below the $9.99/month threshold) — then Scripps can export the model to others of it 19 TV markets. Going into 2014, though, there’s no timetable for doing so. Soon there will be other local TV experimentation to watch. As Press+ (which this week announced its 500th customer) launches its first local TV metered paywall, we’ll see how that experiment progresses as well. The nuances of metered TV sites will be worth watching for newspaper sites as well. In Press+’s TV model, the video meter is a clock — giving, for instance, 10 minutes of free viewing, before watchers hit warning and pay-up screens. The text-story meter is still article-based, so the TV model is a hybrid. The WCPO expansion raises many more questions for the news business. Among them:

Photo of WCPO van by Travis Estell used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Where in the world is BuzzFeed? Building foreign news around themes rather than geography Posted: 05 Dec 2013 07:00 AM PST When BuzzFeed launched BuzzFeed World, an ambitious foreign news vertical, not everyone thought they were up to the task: That link, which is broken, is supposed to take you to a story written by Max Seddon, BuzzFeed’s foreign correspondent in the Ukraine. Seddon was hired by Miriam Elder, who herself spent seven years in Russia before making the move to New York to run BuzzFeed’s world desk. I asked Elder how she would respond to naysayers like Morozov (who, to be fair, has many nays to say). “If that’s what someone thinks our entire foreign coverage is, that just means they haven’t been looking at what we’ve been producing,” she says. “My approach to this is that there’s room for sarcasm, there’s room for humor, and there’s room for incredibly serious and deeply reported stories as well. You don’t have to choose one over the other.” Elder wasn’t always sure BuzzFeed’s unique blend of what she calls “the fun side” and serious journalism was for her. But after over a decade as a foreign correspondent, she found herself increasingly concerned about the status of foreign reporting in the broader journalistic landscape. “Nobody wants to see these foreign desks closing; it was incredibly difficult for me, personally, in Moscow, going to the closing party for the Newsweek bureau or something. It’s not something anybody wants to see, even though they’re technically your competitors,” says Elder. Enticed by what she describes as the intelligence, creativity, and ambition of the BuzzFeed environment, Elder agreed to move to New York to start building BuzzFeed World. Building a foreign desk from scratch is no small task — you have to think about issues like ensuring your correspondents’ safety and getting them health insurance in other countries, things BuzzFeed is committing to providing its reporters. Elder says she’s both sought and received advice from industry old-timers who appreciate that someone, at least, has the cash on hand to be sending reporters abroad. Says Elder, “I don’t see it, at this point, of a challenge between traditional versus new; it’s just putting together a desk is not an easy thing.” Elder embarked on that task by selecting reporters based on which regions BuzzFeed’s editors wanted to cover. She hired Mike Giglio, based in Istanbul, to cover the Syria conflict; Sheera Frenkel to report on the Middle East and northern Africa from Cairo; Max Seddon, currently in the Ukraine, to cover Russia and Rosie Gray to cover foreign policy from D.C. Elder’s next hire was Lester Feder. But unlike the other correspondents, Feder didn’t have a journalistic focus tied to the region that he lived in; the next step wasn’t filling in a few more of the blank spots on the globe. Feder’s focus is on LGBT issues. “It wasn’t the sort of thing where he’d show up in Bangkok or Phnom Penh and be like, This is what the gay scene is like here. It was more focusing on legislative initiatives, interesting activist groups you hadn’t heard of, focusing on the role of third-gender issues in these countries,” says Elder. “He just went so deep into it, it was so impressive, and it was a beat we knew we wanted to keep, so we brought him on full staff.” For BuzzFeed, Feder is based out of D.C.; he takes reporting trips once a month or so. Recently, in addition to reporting on major headlines from Washington, he’s reported stories from Montenegro, Kiev, and Cambodia. Why build a beat around a theme rather than a geographic region? “The idea behind it is kind of, how can you get people really interested in international news?” says Elder. “It’s something that I think a lot of editors ask themselves quite often. I started thinking, you know, if someone is really interested in LGBT rights in the U.S., they’re probably going to be interested in LGBT rights in Russia, in Uganda, in China. It’s this way to explain the world through a thematic vector.” Elder started thinking about other interest areas that could entice readers to get more excited about news around the world, and decided on women’s issues as the next subject to tackle from the global perspective. After a search, she settled on Jina Moore, a reporter usually based in Africa — Nairobi, at the moment — to fill the role of roving women’s issues correspondent. “She’s so impressive, and has so many ideas, everything from incredible reporting ideas to ideas about how to structure news — she thinks really conceptually about these things,” Elder says. “It just ended up being a perfect fit.” With the hiring of everyone from a news director to a Pulitzer-winning investigative reporter, BuzzFeed has been trying to make it clear that its dedication to journalism is the real thing — but even so, the idea of paying for two reporters to jet around the world chasing stories seems a world away from BuzzFeed’s GIFs-and-cats origins. “It’s expensive, but it’s not like we say, Okay Lester, get on a plane, fly first class, and stay at the Ritz,” Elder says. “It’s about having low overhead. The lower the overhead, the more money for the travel budget. But that’s one of the advantages — we have the money right now to be able to fund these sorts of things.” BuzzFeed does, indeed, “have the money” — it raised another $19 million round of venture capital in January, and founder Jonah Peretti reported recently that the site is profitable. But why spend it on traveling reporters with global beats? Elder says that by using hot topic interest areas as a lens through which to view world news, she’s taking advantage of a new behavior that, in some ways, is a direct product of the Internet; she calls it cross border identification.

“If there’s a kid who’s sitting in Russia, and he spends all his time online, he tends to be quite liberal, he listens to this kind of music, he does this, that, or the other — a lot of times he can have more in common with a random kid who’s doing the same thing in Beijing or Oslo or wherever than he does with the guy living down the street from him. The world is being organized in different ways,” Elder says. In addition, the roving reporters’ topic focus can line up better with the heavily verticalized form BuzzFeed’s content takes. A newspaper’s foreign correspondent might cover a country’s politics one day, its industry the next, and local culture the next. BuzzFeed doesn’t have a newspaper’s instinct to be all-inclusive; it picks its spots, and a thematic focus fits in well with that. A topic focus can also make it easier to build source relationships with activists, says Elder. “It almost makes it easier to get stories because…the global activist community, government officials, whomever, knows who to reach out to,” she says. “For activists around the world to have that one person they know that they can come to with their stories, their scoops, with whatever efforts they’re working on, it’s helpful to have one person that can draw on this entire global activist community.” Elder points to Feder’s coverage of the World Congress of Families, a conservative, anti-gay group, as an example of the site’s ability to cover both sides of the issue. “He has really good relationships with them,” Elder says. “They know his coverage tends to focus on the LGBT side.” That said, BuzzFeed hired both Moore and Feder in hopes of tapping into the high levels of enthusiasm and attention that go hand-in-hand with activism. Recently, BuzzFeed has met with criticism regarding the nature of some of its hiring — and firing — in the editorial department. The company hired Isaac Fitzgerald a few weeks ago as editor of its book section, at which time Fitzgerald shared with the world his stance against publishing negative reviews. “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say nothing at all,” he told Poynter. Then, Mark “Copyranter” Duffy spoke out about his firing from BuzzFeed, which, he argued, occurred because the typical tone of his posts — “hating is what I do, and have always done,” he writes — conflicted with BuzzFeed’s strict “no haters” policy. The big picture here is that, from a business perspective, BuzzFeed believes it’s best off if the majority of its content has a positive tone or connects with the perspectives of its audience. “We’re coming from a place where LBGT rights and women’s rights…it’s not like there’s a pro and a con side, really,” Elder says. Elder would like to hire more issues-based, global reporters — perhaps one focused on global corruption — but for the rest of 2013, she’s focused on hiring a national security reporter in D.C. and a deputy foreign editor to be based out of BuzzFeed’s new bureau in London. (BuzzFeed also has a bureau in Australia, as well as content made in New York for audiences in Paris and Brazil, all of which functions separately from the foreign desk.) After that, she’d like to dispatch correspondents to Latin America and Asia, especially China. Overall, BuzzFeed’s foreign story mix seems to continue to match the site’s broader combination of “fun” and news. When Ukraine surprised its neighbors by signing an agreement with Russia, thereby backing away from an agreement with the EU, Max Seddon tackled the national reaction in two ways. First, he scanned the Internet for how people were reacting — mostly humorously — online; then, he hit the streets. “The Internet is infinite,” Elder says. “We can put whatever stories we want up there.” Image by pink hats, red shoes used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Freedom of the Press Foundation wants to help build secure communication tools for journalists Posted: 05 Dec 2013 06:16 AM PST The Freedom of the Press Foundation launched a crowd-funding campaign to support secure communication tools for journalists this morning. In its first year, the foundation has raised more than $480,000 to support investigative journalism projects “focused on transparency and accountability.” This new campaign, which will last two months, is aimed at making communication technology more accessible to journalists by open sourcing tools for encryption in newsrooms, including:

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |