Nieman Journalism Lab |

| The newsonomics of Forbes’ real performance and price potential Posted: 16 Jan 2014 09:28 AM PST The bidding for Forbes is now moving into round two, with a sale expected within a month. A surprising set of largely non-U.S. buyers is flipping through the pages of a memorandum prepared by Deutsche Bank, which Forbes has tasked with shopping the property. A careful reading of that 62-page confidential document reveals a lot about the company’s much-heralded forays into new businesses. It also provides hard numbers that could only be guessed at in the press when Forbes’ owners (the Forbes family with a 55 percent stake and Elevation Partners with the remainder) put the company on the market in November. Buyers expecting either some kind of strategic business model breakthrough or in buying badly needed publishing EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) may be disappointed by the numbers. Revenue is significantly lower than public estimates of this very private company. The numbers show that the boundary-breaking Forbes may be faring a little better than its rivals, but it’s found scaling up both revenues and earnings tough to do. In fact, over the past year, overall revenue growth has been cut in half. That’s got to be a red flag for buyers considering the story Deutsche Bank’s memo tries to lay out. Overall, the numbers should point to the difficulty of obtaining the $400 million price Forbes would like to reach. The magazine company’s earnings just don’t justify anywhere near that valuation. But there is one big asterisk: The three non-U.S. companies that have an interest in heading to the next round may well be prepared to pay a premium for the intangible value of the brand and its global value going forward. We’d expect that the the offering statement would do a dance about Forbes’ identity. It can make the claim that Forbes.com “is the #1 business website,” but in its search to become a native creature of the web, it has softened much of its long-time serious business identity. Not that long ago, in the old print business world, names like Forbes, Fortune, and BusinessWeek went together like CBS, NBC, and ABC, or Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News & World Report. The value proposition was clearer — both for readers and advertisers. It was good to be among the top three periodical chroniclers of American business — or as Forbes came to call itself, “The Capitalist Tool.” In the digital world, Forbes redefined itself. Under Lewis D’Vorkin, its chief product officer, it borrowed as much from The Huffington Post as from Forbes the magazine. (Good D’Vorkin strategy view from The Guardian.) Now its listicles, headlining, wide use of lower-cost contributors, and prominent video evokes BuzzFeed or Business Insider more than Fortune or Bloomberg Businessweek. The content strategy broke through previous bounds, winning both accolades and page-spinning derision; its commercial strategy recognized the value of brand and product extension before other legacy publishers did. The commercial buzz around Forbes.com — and much of the premium it is trying to get from a buyer — centers on three non-traditional businesses:

Forbes, of course, isn’t alone in any of those pursuits. But it is its profound (and early) embrace of several of these strategies beyond traditional ads and circulation that have made a different kind of a name for itself. So one key question in the Forbes sale is this: How much difference have those high-profile businesses made financially? BrandVoice now accounts for some 20-25 percent of the company’s ad revenue, contributing $25 million in 2012. (Let’s use the 2012 final numbers because that’s how Deutsche Bank laid out its data in November, when it released its brief. As round two of bids start coming in, potential buyers should have access to full-year 2013 data. For our purposes, though, 2013 is still “projected.”) That extended range of content brought in $15 million in 2012 over 2011, a growth rate of almost 50 percent. Licensing brought in $10.8 million in 2012, up 24 percent year-over-year. So far, so good. The buzzy initiatives are indeed bringing in new revenue. Overall, Forbes earned an additional $11.9 million in new revenue. To get the extra in new revenue, Forbes had to spend $10.9 million, making a slim $1M in extra EBITDA, or earnings — to $15.3 million from $14.3 million year-over-year. Put simply, Forbes had to spend more to get more: a few million each in editorial, ad sales, and production. As would-be buyers consider offers, they can tell themselves one of two stories about that performance:

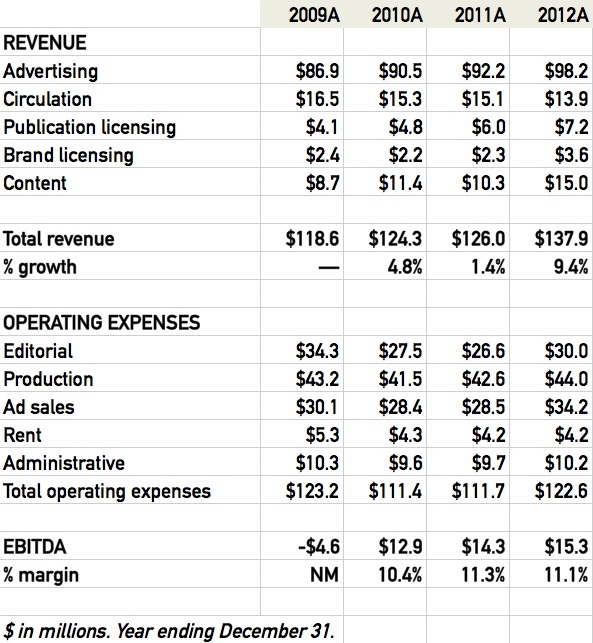

Of course, the Forbes pitch is the former. Look, below, first at its historical finances. Note, especially, the highlighted lines for Total Revenue and EBITDA. The overall revenue numbers are unremarkable: Up 4.8 percent, 1.4 percent, and 9.4 percent in the three years leading up to 2012. Earnings are better at 10.4 percent, 11.3 percent, and 11.1 percent. In fact, the 2012 total revenue of $137.9 million is about half of what the press had cited as Forbes’ annual ad revenues. Maybe the hardest-to-explain number: Projected revenue growth of 4.9 percent for full-year 2013, half the growth rate of the previous year.

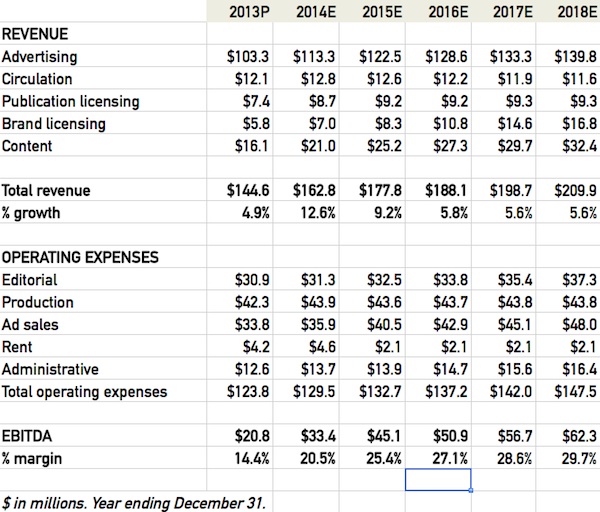

Let’s now look at the projected (2013-2018) numbers. Most striking is the earnings (or EBITDA line). Forbes says they will triple in five years, from $20.8 million to $62.3 million, even though they’ve grown only 25 percent in the last three. But revenue is projected to increase just 45 percent, to $209.9 million from $144.6 million. In the offering memo, Forbes doesn’t clearly explain why its projected cost increases are so much lower than its revenue increases.

As important as the projections is the changing marketplace Forbes operated in. Forbes.com’s ad revenue is projected to move from $42 million in 2012 to $86 million in 2018. “Display advertising impressions are expected to increase in 2013 with rising traffic worldwide, and doubling of site visits resulting from increasing smartphone use. Increase in available display impressions, number of BrandVoice partners and success of the programmatic sales effort is expected to drive this increase in advertising revenue. Revenue is projected to grow at a CAGR of 8.7% through 2018 via a combination of increased traffic, new engaging products, improved sell-through at relatively steady rates and increased performance in programmatic sales.” That is, in one word, optimistic. As Deutsche Bank warns in its introduction: “This Memorandum includes certain statements, estimates and projections provided by Client with respect to its management’s subjective views of its anticipated future performance…These projections have not been independently verified and cannot be regarded as forecasts.” It’s boilerplate, but for those of us who have plowed through docs like this over the years, it’s worth remembering. It’s true that Forbes can claim an impressive 16 percent digital ad revenue increase year-over-year, one that largely tracks the broader digital ad expansion. That digital ad revenue now represents 43 percent of all ad revenue. (Weighed down by print ad declines, overall ad revenue is up 6.5 percent.) But Forbes not only faces direct digital ad competition within the “business news” sector — Fortune, WSJ, Bloomberg, CNN, Quartz, and more — but also for affluent readers more generally. The top six ad players, led by Google, can now all target those audiences, and they claim to do it more efficiently and cheaply. That’s why digital ad growth has slowed for the great majority of publishers. ARPU — or average revenue per user — is also facing downward pressure (“The newsonomics of ARPU”). Yes, mobile usage is increasing audience and time spent with news sites — but more time isn’t tracking with more dollars (or euros or pounds) spent. The numbers prove it: Forbes says it is up 35 percent in unique visitors worldwide, but its revenue growth is no more than a quarter of that number. Overall, this is still an ad-dependent business, and that could be problematic in the years ahead. Ads account for 71 percent of its income in 2012, down only two percentage points from 2011. That’s because circulation revenue keeps dropping, to $13.9 million in 2012 — down $2.6 million in three years, or 8 percent in the last two years. Let’s remember that Forbes is free in the digital world; its strategy has long been about spinning more and more pageviews, one way or another. That means that unlike its competitors, which can charge for all-access or digital-only subs, Forbes has no easy route forward for substantial digital reader revenue. (Its paid niche investing newsletters are a good idea, but will throw off less money than an overall paid digital strategy.) Inevitably, that tilts it toward ad dependence, just as many other news publishers are running the other way. Hearst Magazines’ David Carey (“The newsonomics of Heart’s one million new customers”) has been clearest on that point in the consumer magazine world. Leading newspapers like The New York Times and the Financial Times have trumpeted their arrival in the majority-reader-revenue camp. Other revenue projections demand superior execution against growing competition as well. What the memo terms “Content” (a.k.a. conferences, newsletters, and research) is slated to double. While Forbes pioneered native advertising and got into custom research and conferences earlier than most legacy publishers, the competition in each of those areas is intensifying. There is a limit, after all, to the number of conferences people can go to. Which brings us back to profit. If the revenue growth assumptions might be a little rosy, especially in 2014 and 2015 (12.6 percent and 9.2 percent), the expense projections don’t seem to match up with the efforts needed to get the new revenue. They are all conservative, leading to a 29.7 percent EBITDA projection in 2018. (Its rental cost assumptions now can be newly defined; Forbes surprised its Greenwich Village-based staff yesterday by announcing a move to a Jersey City “media center.”) So what do the numbers tell us about a likely buyer, or price? As Forbes heads toward a sale, it’s telling that no U.S. publisher seems much interested. But it’s not surprising. On the basis of its operating results, its price tag is too high. The enthusiasm is largely from outside the U.S., according to a good piece by William Launder in The Wall Street Journal. One is from a serious publisher, Axel Springer, Germany’s largest publicly owned news company. Springer is rapidly transforming its portfolio (“The newsonomics of the German press’ tipping year”) and already licenses the Forbes name for Russian and Polish editions, among others. The Journal cites two other Asian companies, Fosun (the “Berkshire Hathaway of China”) and Singapore-based Spice Global Pvt. Ltd. as the other likely finalists. Fosun, like Springer, already licenses the Forbes name for a Chinese edition. Of course, both licensees — Springer and Fosun — could presumably continue to license “Forbes,” rather than buy the company. Why would they buy? We could look at the potential non-U.S. buy of Forbes as a trophy acquisition. For non-U.S., non-publisher buyers, buying media can be just as much about power as it is money. Last month, Chinese recycling magnate Chen Guangbiao minced no words when he said his unsolicited offer for The New York Times was as much about influence as business. (“Every government and embassy, all around the world, pays attention to The New York Times.”) Given this cast of potential characters, though, there’s more nuance in the buying motivations. Maybe it would be more accurate to say that a great brand — globally and differently purposed — could be of more potential value to a buyer than the current operating performance of a publication itself. Calling itself a “96-year-old revered brand” may be a tad too self-congratulatory, but there’s clearly European, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American value to a print brand that may have seen its best days in the United States. IBT bought a tired Newsweek for a virtual song, but sees value in that well-known title as it prepares to relaunch it early this year. Jeff Bezos “overpaid” for The Washington Post if you evaluate it purely on earnings, but he knew that a price tag of $250 million for the Post brand was a steal. (Axel Springer CEO Mathias Döpfner said last year he would have liked the opportunity to bid on the Post.) The usual multiple for pricing magazines would be 5× or 6×. But Forbes wants a digital multiple — 10× or more — not a magazine one. Consequently, in November, we heard that ownership expected $400 million as a sales price. Now the FT has reported that the price could be between $350 million and $475 million, as the number of bidders trims from the 18 companies that took a look at the financials. At $400 million, that would be about 26× of the $15 million 2012 earnings. Even at a more reasonable $200 million, that would be 13× earnings. If the $400 million price holds, it looks like the value of global brand potential will make up half of the price of this deal. Photo of Forbes headquarters in New York by Rafael Chamorro used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Will 2014 be the year the Banyan Project finally takes flight? Posted: 16 Jan 2014 07:00 AM PST Having overcome a series of logistical obstacles, Haverhill Matters, the Banyan Project's long-delayed demonstration site, appears to be on track to launch sometime in 2014. Banyan's founder, veteran journalist Tom Stites, hopes the pilot will foster the rise of local news organizations that would be cooperatively owned and managed, similar to food co-ops and credit unions. "We enter 2014 with some momentum. We've got to keep it. We've got to build it. We've been picking away at this thing for a couple of years," Stites said at an organizational meeting on Tuesday evening. "This is the kickoff, right now here tonight, of the pivotal year. If we don't do it this year, chances are it won't get done." For some years now, Stites, who's worked as an editor at The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune among other places, has talked about fostering news co-ops in so-called news deserts: communities underserved by traditional media. (Here's a story I wrote for the Lab about Banyan's Haverhill plans in 2012, and here's a followup I wrote last May.) Haverhill, a city of about 60,000 in the Merrimack Valley north of Boston, is covered by a corporate daily and an affiliated weekly, both of which are headquartered in nearby North Andover. The city is also home to an online radio station currently seeking a low-power FM license and a robust community television operation, both of which will partner with Haverhill Matters. Since last spring, a committee of local volunteers has been working to get Haverhill Matters off the ground. At Tuesday’s meeting, held on the Haverhill campus of Northern Essex Community College, Stites and seven committee members agreed on a rough timetable:

Reaching the $50,000 threshold will trigger something else as well — the site's first journalism project. Stites proposes asking the co-op's members for ideas about a significant piece of enterprise reporting. Those ideas will be put up for a vote, and a freelance journalist will undertake the winning assignment, all the while soliciting the community for suggestions, documents, and the like. The goal, Stites said, is to use the crowdsourced reporting project to generate more interest in the project. Anyone will be able to read Haverhill Matters for free. But in order to post comments and take part in the site's online community, people will have to become members — either by paying $36 a year for an individual membership or, as with a food co-op, contributing labor. But rather than bagging groceries, a Haverhill Matters member might write a neighborhood blog. Fully staffed, the site would have a full-time editor, a full-time general manager who would also be engaged in the journalistic side and a part-time office manager who could also offer technical support. The process laid out Tuesday was a somewhat convoluted one, which brought some sharp observations from Amy Callahan, an English professor who runs the journalism/communications program at Northern Essex. Her basic question: Why not start a small, minimally funded news site as soon as possible and give it a chance to grow over time? Why wait until $50,000 is in the bank? Callahan's questions were good ones. But having watched the process unfold since last April, I've come to see that launching a co-op is not a simple matter. There are numerous rules and regulations that must be followed in order to make sure that it's viable and run by the members. Starting a nonprofit or for-profit news site is simple by comparison. I can also understand the need to hire and pay a full-time organizer. "I'd love to believe it could be done more incrementally," said committee co-chair Mike LaBonte. But the site needs a paid organizer, he added, "because we've been doing this with the spare time we don't have." If Haverhill Matters succeeds, Stites hopes it will lead to news co-ops around the country. The Banyan Project, a nonprofit1, would sell these nascent co-ops software and advice, which Stites believes would make it easier for local organizers. Haverhill Matters would not be the first news co-op (that distinction belongs to a site in Hawaii), though its status as the pilot for a more ambitious project makes it notable. There's no question that innovative approaches to providing local news are needed. Newspapers continue to struggle. AOL wiped Patch off its books Wednesday, spinning it off and handing majority control to an outside investment firm. And though there are a number of independent local news sites, there's a ceiling on how many are feasible: Few people possess the necessary combination of journalistic skills, technological acumen, and entrepreneurial ambition to run one successfully. Banyan promises something different — community news produced by a community-owned news organization. That's why it's worth keeping an eye on Haverhill in 2014. Dan Kennedy is an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University and a panelist on Beat the Press, a weekly media program on WGBH-TV Boston. His blog, Media Nation, is online at dankennedy.net. His most recent book, The Wired City: Reimagining Journalism and Civic Life in the Post-Newspaper Age (University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), tracks the rise of online community news projects. Photo of banyan tree by Jeff Stvan used under a Creative Commons license. Notes

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |