Nieman Journalism Lab |

- J-schools: Success in news today is about a lot more than reporting and writing

- Cut loose by UC Berkeley, hyperlocal site Mission Local looks to spin off as a for-profit

- The newsonomics of the print orphanage — Tribune’s and Time Inc.’s

- The new Knight News Challenge focuses on strengthening the free and open Internet

| J-schools: Success in news today is about a lot more than reporting and writing Posted: 27 Feb 2014 11:56 AM PST The decision by the University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism to cut loose Mission Local, one of the three local news sites it used to train journalists, is sad but unsurprising. The school faces plenty of financial pressure and the costs of running the sites — funded initially by grants from the Ford Foundation — has long been an issue. In a memo to the journalism school community, Dean Edward Wasserman gave a number of reasons for the decision. He cites costs and the distance between the Mission District in San Francisco and the school’s base on the Berkeley campus. Wasserman’s third reason, however, was particularly disheartening.

I have a dog in this fight, as one of the founders of Berkeleyside, an independent, local news site in Berkeley. Our ability to report the news remains at the core of what we do, but without awareness, adaptability, and a modicum of skill in those “specialized areas,” we would have sunk without a trace very quickly. The same equation is true for anyone working at the many new ventures in journalism, even when they are vastly better capitalized than Berkeleyside, whether it’s Walt Mossberg and Kara Swisher at Recode, Ezra Klein at Project X, or Sarah Lacy at Pando. What was so encouraging about Mission Local and its equivalents was that they gave j-school students a much better approximation of the real world of journalism today than internships in big newsrooms. It’s a crazy scramble with scarce resources, juggling traditional reporting, video, and social media with hands-on engagement, building community and partnerships, figuring out the place of events, understanding the need for revenue, and so much more. I don’t expect every j-school graduate to create their own news operation, but I hope some of them eventually do. I’m certain, as well, that the majority of them will need to be familiar with those 1,001 other tasks if they are to thrive in the media world that is being formed today. The alternative, suggested by “That’s not really what we do,” is to rely on graduates schooled in business or technology to forge the new models that journalism needs. Let the Tim Armstrongs of the world figure it out. I’d rather see the journalists take the lead. Lance Knobel is a founder of Berkeleyside, the independent local news site for Berkeley, CA, and curator of the Berkeleyside-run Uncharted: The Berkeley Festival of Ideas. Photo of gathered reporters by Philippe Moreau Chevrolet used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Cut loose by UC Berkeley, hyperlocal site Mission Local looks to spin off as a for-profit Posted: 27 Feb 2014 11:56 AM PST Five years ago, in the worst days of the economic collapse, Len Downie and Michael Schudson wrote their benchmark report “The Reconstruction of American Journalism,” attempting to chart a course forward for a news business in trouble. One of their major recommendations was that universities should become more engaged in producing reporting for their communities. If their teaching hospitals could both train future doctors and serve the public’s health, why couldn’t journalism schools fill some of the holes newspapers were leaving behind while training future reporters? One of the examples Downie and Schudson cited favorably was the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley, where journalism students were “reporting in several San Francisco area communities for the school's neighborhood news Web sites.” While some j-schools have embraced the teaching hospital model, this week Berkeley announced that one of those neighborhood sites, Mission Local, would no longer be attached to the j-school. Instead, it’ll be spun off at a private entity with a less-than-certain future, no longer getting student reporters as part of the school’s course offerings. Dean Edward Wasserman said in a memo that the move was prompted by Mission Local’s cost and because it distracted students from the core curriculum of the program. The site, which covers San Francisco's Mission District, will relaunch as a for-profit. "It's now time for Mission Local to take the next step and re-launch itself as an independent, stand-alone media operation," Wasserman wrote. "That means ending its role in the J-School's curriculum. While [Berkeley professor Lydia] Chavez would have liked to see the school keep the site, she is ready to assume responsibility for the site, and we expect that it will continue under her ownership." Chavez said the site will continue to experiment and try to find a sustainable model to support quality local journalism and provide young journalists learning opportunities. She said she’s in the process of seeking investors; she declined to discuss her plans in depth, as they are still in the works. “It would've been wonderful to have this site, to have all of the sites, really continue to experiment and grow in the community that we're in and to represent Berkeley, but you have have to have someone who is really strongly behind them, and the new dean is not,” Chavez told me. “He has other ideas that I'm sure will be exciting, so we'll see what his ideas are.” With funding from the Ford Foundation, Berkeley launched Mission Local in 2008 — along with a number of other sites covering other underserved neighborhoods in the Bay Area — to provide students with hands-on reporting experience in communities that are not typically covered by larger outlets. Whether the school will continue to support Oakland North and Richmond Confidential, its two other hyperlocal sites, is "up in the air at the moment" as the school reconsiders its curriculum, Wasserman wrote. In his memo, Wasserman, who was appointed dean in January 2013, gave three specific reasons for ending Berkeley's involvement with Mission Local:

Wasserman did not respond to several requests for comment. The teaching hospital model has gotten a lot of attention in recent years, in large part because of the work of the Knight Foundation's Eric Newton and others in philanthropy who see local coverage as a useful extension of j-school’s educational mission. (Disclosure: Knight is a funder of Nieman Lab.) Jan Schaffer, executive director of J-Lab at American University, said that Mission Local has been among the best of its kind. Schaffer lauded Mission Local's frequent updates as well as its attempts to experiment with different products in various mediums. "Nobody else that I know of does that," she said. "Nobody else that I know of does that level of content." She said that sites like Mission Local are about “learning it on the ground. Learning it everyday. Learning how you distribute a hard copy newspaper, how many donations are coming, how many volunteers you need to make it work, how to write a grant proposal, how to sell an ad. Even if they're not themselves doing that, just an awareness of that landscape is very valuable.” Many, including a number of former Berkeley students, said they were concerned about how the school would replace Mission Local in the curriculum: Still, Wasserman emphasized in his memo that the school would continue to prioritized educating students on the business of journalism as well as on “improving on what we've done in the past, and making sure the future offers opportunities here at least as rewarding and memorable as theirs have been.” Photo of a Mission District mural by Gwendolen Tee used under a Creative Commons license. |

| The newsonomics of the print orphanage — Tribune’s and Time Inc.’s Posted: 27 Feb 2014 08:21 AM PST Talk about spin. Two of America’s once-iconic publishers are about to be spun. Spun off, that is, from parent companies that have fallen out of love with print and in love with moving pictures. The names of the Chicago Tribune and Time magazine may invoke the publishing golden age birthed by the Colonel McCormicks and Henry Luces, but these publishing divisions today are more than tarnished. They’ve become liabilities, weights on future enterprise,and anchors of low profitability as advertising revenues continue to be eaten away by the Googles and Facebooks of this era. Tribune Company and Time Warner will move on without their namesakes, a plaque or two in the lobby remaining behind to commemorate their illustrious histories. What we’re seeing unfold this year is an orphaning of distressed publishing assets: setting them adrift in an inhospitable business climate, thinly clothed and with a heavy bag. Call it publishing orphanage. It’s a noteworthy moment in an almost decade-long reckoning with the long slide in both the newspaper and magazine industries. Both Time Warner and Tribune are working through all the financial and legal issues en route to hiving off their publishing assets from their core TV/movies/digital businesses. Both should have the process completed by the middle of the year, probably a little earlier. Both are following in the footsteps of other media splits, including 2013′s News Corp. and 2007′s Belo and Scripps. But both are planning on putting more of a burden on their publishing businesses than we’ve seen in previous splits, with Tribune’s approach standing out as particularly Dickensian. In essence, it’s a newer, harsher reality for legacy news operations forced to live on their own. In part, that’s a reflection of the challenges that the non-print sides of Time Warner and Tribune face. Adjusted operating income was down in 2013 for Time Warner’s HBO and Turner divisions and at Tribune’s broadcast operations. Yes, publishing may be distressed — but the TV/video path forward is chockful of competitors too, taking money and customers away at every opportunity. Both Time Warner and Tribune are assigning significant debt to their split-off companies. But debt is only part of the story. The burdens being placed on standalone Time Inc. and Tribune Publishing are several-fold:

To be fair, Tribune has noted in its filings that parent “Tribune is also expected to retain most of its pension assets and liabilities.” We’ll have to wait and see what “most” means.

So, to the question of the day: What difference will the split arrangements have on the journalism that the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Tribune’s six other metro dailies produce? What are the chances that Time Inc.’s Time, Fortune, Sports Illustrated, and Entertainment Weekly, among others, will be able to find a high-quality print/digital way forward? Will the readers of those publications be affected by the new financial obligations of the publishers? The answer is painfully simple: Yes. By one measure, the new debt put on the publishing companies is reasonable. Time Warner’s overall debt is $18.3 billion; it is assigning 7 percent of it to Time Inc. Tribune’s overall debt is $4.1 billion, most of which was incurred in its purchase of Local TV stations last fall; it is assigning 8 percent of it to Tribune Publishing. Both new companies, as others have argued, have sufficient cash flow to make the debt service. We can also add to the justification that as divisions of larger media companies, both publishing divisions contributed to debt service all along. But that argument ignores the reality of 2014. Both publishers have only remained profitable by significant staff cutting. Given that revenues will continue to be down this year for both, somewhere in the mid single digit range, they’ll have to continue cutting costs and staff to maintain profitability. The new debt service and lease obligations won’t break their backs, but they’ll be added new weight on backs already bent. That’s in contrast to those other recent publishing splits which were more friendly to the print half. The most recent and instructive parallel is last year’s News Corp. split. Pushed by shareholders and Hackgate fallout to split his baby, Rupert Murdoch steered $2.6 billion in cash to the newspaper-heavy company and freed 21st Century Fox to head off into its future. The new News Corp wasn’t assigned any debt, didn’t have to pay a dividend, and kept all the real estate underneath its newspapers. Further, Murdoch threw Fox Sports Australia and digital real estate services into the new “newspaper” company, giving it a couple of growth drivers. Seven years ago, when Belo split off its newspapers as A.H. Belo, it assigned no debt to the newspaper split. Also in 2007, Scripps separated out its newspaper and broadcast properties from its high-flying cable ones. In that case, the new cable business, Scripps Network Interactive, got $325 million of the debt and E.W. Scripps, the new newspaper/broadcast entity, got $50 million of it. Neither Scripps nor Belo separated the real estate from the legacy operations. Why? All three companies realized that the standalone newspaper entities needed every dollar possible to find a future. Arguably, the editorial operations of The Wall Street Journal, The Dallas Morning News, and Naples Daily News are better off for it today. Will we be able to say the same when the Chicago Tribune, L.A. Times, Baltimore Sun, and Orlando Sentinel are set adrift? A few inquiring minds want to know. One of those is Henry Waxman, the Democratic ranking member on the House Energy and Commerce Committee. Waxman raised an alarm about the Tribune’s assignment of debt and dividend to its spinoff back in December. While newspaper business matters generally fall outside the purview of Congress and regulators, the committee does provide oversight of the Federal Communications Commission. Waxman’s interest, though, is more local: The long time L.A. congressman worries about the future of the local L.A. Times. So Waxman has met with Tribune CEO Peter Liguori, and formally requested documents related to many of the burdens I listed above. There have likely been other staff interactions, and there may be more to come. Waxman is trying to bring a political moral suasion to the Trib spinoff, asking what indeed will be the impact of the Tribune Company’s stripping assets of every kind — terrestrial, digital, and financial — from the newspapers. But common sense here is paramount. Almost all legacy publishing companies are, to use the polite term, mature enterprises. More precisely, year after year, they take in less money than they did the year before and the year before that. There’s no extra cash lying around. The meager cash flows of these companies goes to:

Think of these four as mouths to feed. Publishers must ration food among them, and there’s not enough. So the short answer to the question: Yes, imposing new costs — debt service, dividend payments, or lease costs — on these spinoffs will make life harder. While life gets harder, more staff — including more journalists — get cut. The road ahead for Tribune Publishing and Time Inc. will be harder if the proposed debt and dividend plans proceed. The journalistic output is likely to suffer. Readers and communities will get less and less experienced reporting. Let’s do some math, first looking at the Tribune context and its numbers. First, there’s Tribune’s heavy cutting pre-split. In late 2013, the company announced a $100 million cost-cutting plan in its publishing division. That resulted in the elimination of 700 jobs across the eight newspapers, on top of 800 job cuts in 2012. The company made a point of saying that newsroom cuts were a small part of those layoffs, but we know there were at least dozens of them, all on top of cuts that have greatly reduced newsrooms from Hartford to Fort Lauderdale through the Sam Zell era (“The newsonomics of the Tribune’s metro agony”). Just as one example, the Baltimore Sun has dropped to fewer than 140 journalists from a peak of more than 400. Tribune has some cash, but it’s not expected to give any of it to the publishing entity. The most recent financials we have for Tribune show that the company has about $700 million in cash and cash equivalents. Now let’s look at the percentage of profits that may need to go to servicing debt and how much debt service could equal in terms of jobs. Overall, Tribune Publishing generated $150 million in operating profit for the first three quarters of the year, so we can extrapolate $200 million for the full year 2013. Or course, what generated those profits is cost-cutting. To get to that level of profit, it reduced expenses 13 percent — including 230 positions. The new Tribune Publishing can continue to cut — but a further 13 percent would simply continue the hollowing-out process of the company and its newsrooms. Importantly, Tribune’s newspapers aren’t steady state: Revenues continue to fall. Now the new debt service. Let’s say that Tribune Publishing will need to borrow $650 million overall, with half of that borrowing going immediately to Tribune Company as that “special dividend.” What might it pay for that money? Lee Enterprises, considered a large well-managed newspaper company, recently refinanced its own debt at 12 percent. (That was actually lowered from 15 percent.) Tribune may have access to cheaper money; let’s say it wrangles a 10 percent rate for the new, market-challenged newspaper company. That’s a payment of $65 million a year — or a full third of those 2013 profits. That’s more weight on Tribune newspapers back. Now let’s consider individual backs and calculate that number in terms of jobs. At an average of, say, $75,000 a year, that’s 866 jobs. That’s out of total of more than 8,000 full-time publishing division jobs. The arithmetic is fairly straightforward. The obligatory debt service could be paid for by having 900 or so fewer employees. Let’s say it can limit its new initial debt to $500 million. That would still mean more than 650 jobs. In striving to make the point that it is trying to preserve journalist jobs, the company has pointed out that many of its cuts were in marketing and technology. That may be good for the journalists who would otherwise have been pink-slipped — but those are also two areas where news organizations of the future need more smart investment, not less. In addition, journalist jobs continue to be cut back, even if they are a smaller proportion of the total cuts.

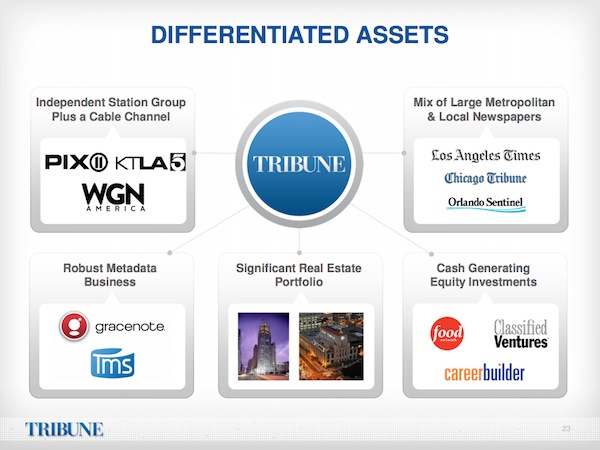

Now let’s look at Time Inc.’s numbers. Time Warner just announced its full-year earnings. To get an apples-to-apples comparison, we take out the new revenues driven by its fall acquisition of American Express Publishing. For the year, revenue was down about 5 percent, and 8 percent for Q4. Both ad and circulation revenues are tumbling. Time Inc., under new CEO Joe Ripp, has also been cutting in anticipation of going solo. Recently, layoffs of 500 employees, or 6 percent of Time Inc.’s staff, were announced. Ripp has also greatly reorganized the leadership team, putting some impressive new talent in place in key exec and product roles. Just today, we see the poaching of Scott Havens, a highly regarded architect of The Atlantic’s renaissance, who becomes senior vice president for digital. What effect might that $1.3 billion in debt have on the ability of that new team to transform Time Inc. into a growth company? Time Warner may well get a better interest rate for its orphan than Tribune, according to knowledgeable observers. Let’s peg it at 7.5 percent. That would create an annual debt service of $97.5 million. That’s the equivalent of 1,300 jobs — or another 12 percent or so — of Time Inc.’s workforce, if and as revenues continue to decline. There are lots of moving numbers here, but the point is clear: As standalone companies with ever-falling revenue, each will have a more direct responsibility for paying off debt, and the likeliest place to pay for it may well be more aggressive staff cuts. Both Time Warner and the Tribune Company have legal obligations is to maximize shareholder benefit; as recently as this week, a hedge fund began pushing Tribune CEO Peter Ligouri to sell any Tribune asset he can. In these splits, though, we have current shareholders who will have their shares divided. Presumably, from a shareholder point of view, both TW and TRB would want to maximize the chances of both new companies prospering and rewarding shareholders. Is the burden being placed on the spun newspaper assets prudent, given their marketplace and transformation challenges? For Tribune, it’s clear that it is going to the spinoff route as a way to save on capital gains taxes when the newspapers are sold. (There are complicated tax issues involved in the spin, which you’ll recall came after the Koch Brothers summer spectacular of 2013 — but observers point to a likely sale of the newspapers not long after the spinoff.) For the current Tribune Company and board, the newspapers appear to be a soon-top-be-dispatched afterthought — one they don’t want to shine much of a light on. Just on Monday, at the J.P. Morgan Global High Yield and Leveraged Finance Conference in Miami, Tribune made its presentation. Given that the company is going mainly TV, most of the PowerPoint’s 25 slides were devoted to broadcast, with real estate, digital properties, and syndication businesses highlighted as well.

In the three slides it devoted to publishing, it highlighted but three fairly broad numbers, with two speaking to a 20th-century audience — and none speaking of dollars and cents.

The new Tribune is ready to be done with the old Tribune, just as Time Warner can hardly wait to jettison Time Inc. — showing its Q4 and full-year financials both with and without the publishing assets. The divorces are about to be decreed, and terms of disendearment betray a lost love. |

| The new Knight News Challenge focuses on strengthening the free and open Internet Posted: 27 Feb 2014 06:00 AM PST The Knight Foundation wants to delay the death of the Internet as we know it — at least for a little while longer. Today Knight is launching the latest installment of its Knight News Challenge, and this round will focus on a subject on many minds these days: how best to support a free and open Internet. Specifically, Knight is asking people how they would answer this question: “How can we strengthen the Internet for free expression and innovation?” Those who come up with a good answer — or at least an idea that can pass muster with Knight’s experts and advisers — will get a share of $2.75 million. Knight has funded the contest for media innovation since 2007 and awarded more than $37 million over that span. This time around, Knight is partnering with Ford Foundation and Mozilla to administer the News Challenge. The contest is open to anyone, with a simple application form on newschallenge.org, with a deadline of March 18. Winners of the News Challenge will be announced at the annual MIT-Knight Civic Media Conference this June. With the FCC attempting to rewrite its open Internet rules after having them struck down by a federal appeals judge, and the pending merger of cable companies Comcast and Time Warner (not to mention Netflix brokering a deal for better service on Comcast broadband network), there has been growing concern about the future of the Internet from consumer advocates and other technology watchers. (Not to mention those three letters N, S, and A and attendant concerns about surveillance and privacy.) “We see the Internet as a really important resource for expression, for learning, for journalism, for connecting to one another as neighbors in the community — we want to make that stronger,” said John Bracken, Knight’s director of journalism and media innovation. With the events of the past few weeks, the News Challenge might seem particularly timely, but Bracken said protecting the free flow of information has been among Knight’s main concerns for years. He pointed to the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy, a collaboration with the Aspen Institute that aimed to “maximize the availability and flow of credible local information” and “enhance access and capacity to use the new tools of knowledge and exchange.” Bracken said recent events will only add more urgency to the News Challenge. “Clearly it’s a topic on a lot of people’s minds,” he said. “It’ll be exciting to see what it yields in terms of ideas and broadening our idea of the topic.” In the most recent round of the News Challenge, which focused on health, applicants were asked to answer the question “How can we harness data and information for the health of communities?” The latest round offers a similarly open-ended question on the subject of the Internet. Bracken said that was done be design to try to spur as many new ideas as possible. (Knight is again using IDEO’s OI Engine to channel ideas through the contest.) Making the ask appealing is one part of the equation; another is taking an active approach to finding people to apply. One of the reasons Knight partnered with Mozilla and Ford is to tie into their networks. In the Venn diagram the three organizations share, Internet openness and democratic access to information slots nicely into the middle. Knight and Mozilla already collaborate on the Knight-Mozilla OpenNews. “We want to expand the network of people we’re reaching. You look at the Internet and open web and building useful tools, and Mozilla and their community come to mind,” Bracken said. Bringing partners into the News Challenge is only the latest tweak Knight has made to the competition in the last several years as it re-evaluates the way it funds innovation in journalism. Since 2012, the News Challenge has been broken up from one annual call into smaller, shorter, themed contests. But the long-term future of the News Challenge remains under examination. (As Knight president and CEO Alberto Ibargüen said at the MIT-Knight Civic Media conference last year: “It may be finished. It may be that, as a device for doing something, it may be that we've gone as far as we can take it.”) Bracken said they’re still re-tooling the competition, as well as expanding the funding opportunities for new projects through other programs like the Knight Prototype Fund. “We want to constantly extend the network of people we work with, and one way to do that is collaborating on a new News Challenge,” Bracken said. Full disclosure: The Knight Foundation is a funder of Nieman Lab, though not through the News Challenge. Image by Roo Reynolds used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |