Nieman Journalism Lab |

| You won’t believe Upworthy’s new way of measuring audience engagement until you read it Posted: 06 Feb 2014 07:33 AM PST Upworthy wants to be known as the company that shares a massive amount of socially conscious content across the web. What Upworthy is widely known for, however, is perfecting the art of the clickbait, curiosity gap headline. (On the front page now: “The Perfect Reply A Girl Can Give To The Question ‘What’s Your Favorite Position?’” “What If Everyone Who Reacted Negatively To A Super Bowl Ad Knew The Facts? They’d Learn This.” “A 16-Year-Old Explains Why Everything You Thought You Knew About Beauty May Be Wrong. With Math.”) The company denies that they’re the main culprit, and some initial research by The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer suggests that may be true. But now, they’re taking steps toward measuring their performance through something deeper than clicks. This morning, Upworthy announced it would be using a new metric — “attention minutes” — as its primary tool to determine how they’re doing. The goal is to blend traditional eyeball-counting metrics with figures that more accurately measure engagement or how much the audience actually likes the content that they’re making. And they’ll be releasing their source code so other publishers can use it.

Upworthy says they decided to build attention minutes in the fall out of frustration with available analytics, either because they measure the wrong things or because they measured them poorly. For example, while Google Analytics’ time-on-site metric seems like it should provide something like what Upworthy was looking for, it was often misrepresentative, calculating at one point that the average Upworthy user spent 21 minutes on site. (“We're good, but we know we're not that good,” they write.) Of course, Upworthy isn’t the only publisher feeling disatisfied with the mighty pageview and its many successors. Former Knight-Mozilla OpenNews fellow Brian Abelson, who now works at Enigma, spent part of his fellowship at The New York Times working on “pageviews above replacement,” a method of looking at basic traffic results without the confounding factor of internal promotion. James Robinson, director of news analytics at the Times, had this to say about metrics in his Nieman Lab prediction for news in 2014:

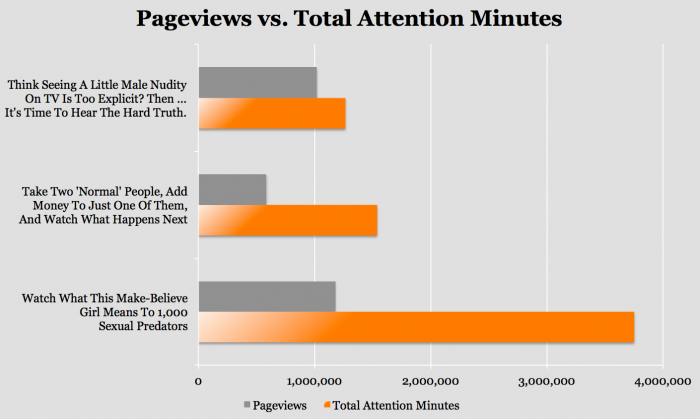

As Upworthy acknowledges, other media companies have also begun to make moves towards more meaningful metrics. “There are definitely others looking at how to improve metrics,” writes Upworthy CEO Eli Pariser in an email, citing YouTube’s “Time Watched,” Medium’s “Total Time Reading,” and Chartbeat’s “Average Engaged Time.” (Chartbeat responded to Upworthy’s announcement on their own blog, calling the metric “another big win.”) “They all have a similar hunch,” Pariser said. “As we’ve been building it out it’s been nice to see additional traction on this front. It gives us a sense we’re not way out in left field.” Attention minutes are calculated using an assemblage of what Upworthy calls “signals.” Pariser says they started out by asking, “What are the ways you can know if it’s a sad, lonely, ignored tab or if someone is watching intently?” Some of these signals include the length of time a browser tab has been open, how long a video player has been running, and the movement of the mouse on screen. “This method doesn't store raw information — it follows a stream of events and every few seconds asks, ‘Is this person still paying attention?’” Pariser said. “If they are, that sends a signal to a data warehouse that says, ‘Chalk up a few more attention seconds for this post.’” Together with other information, including pageviews, Upworthy hopes to get a sense of what content is most delighting and engrossing viewers, not just briefly capturing their attention. This chart is meant to illustrate how the signals that make up attention minutes present a significantly different portrait of a story than pageviews do:

Upworthy plans to release the source code “in the coming months.” Pariser says Upworthy has already begun to gather valuable information about how people consume content — like that “the relationship between the length of a video and how much people watch isn’t what we though it would be,” he says. They’ll be publishing more of that information in 2014, too. The overarching hope is that by improving the quality of your metrics, you can improve the quality of your work. Campbell’s Law puts it well, if academically:

If you measure performance in pageviews, you encourage slideshows. If you measure performance by social shares, you encourage clickbait headlines and giant Like buttons. Finding a metric that lines up with a publisher’s goals is one of the most important things it can do to encourage better work, and Upworthy thinks this is a step closer to that alignment for their needs. “The reason that we’re focused on this metric is not just because we think it’s good for us, but because we think it would serve everybody better if we moved away from some of the metrics that people have been using,” Pariser says. “Pageviews can be bought, but this…is a truer measure of whether you’re delivering something meaningful and valuable.” |

| The newsonomics of The Guardian’s new “Known” strategy Posted: 06 Feb 2014 07:00 AM PST LONDON — The Guardian is an enigma. Long a storied editorial brand, it’s been propelled toward the top of global news audience, both by its open strategy and its hard-nosed journalism. In the past year, it’s broken story after story on NSA spying as the primary recipient of the Edward Snowden files. It’s also expanded its efforts in both the U.S. and Australia, enlarging its global readership. With “open” as its watchword, The Guardian has pushed into every nook and cranny of the social sphere, as cataloged here at the Lab. But it’s also the Rodney Dangerfield of commercial journalism: It gets no respect. That contradiction — between a worldwide reach and respect and a business strategy that has seemed unstrategic — may be passing into history. Consider its Known Strategy. Laid out for me by Guardian News & Media’s David Pemsel, it’s aimed at closing that wide chasm between The Guardian’s two faces. Smartly, it intends to leverage the great “open” position of The Guardian rather than fight it. In brief, it’s intended to make business sense of that great Guardian global reach of nearly 40 million monthly unique visitors, shaking off their anonymity (within The Guardian’s own code of privacy and ethics, course) and making them “known” to The Guardian. Let’s look at the mechanics of the Known Strategy — but first, let’s consider its context. Start with Pemsel, a fast riser in the organization. Hired as chief marketing officer in 2011, he became first chief commercial officer and then, in December, deputy chief executive to CEO Andrew Miller. His twin backgrounds: television (ITV) and marketing. Pemsel grew up with the paper; his father, who worked at the BBC, identified with The Guardian’s rebellious streak. That’s characteristic of even the people on The Guardian’s commercial side: They identify with the company as a cause as much as a place to draw a paycheck. “The world’s leading liberal voice,” as it still proudly calls itself, remains a company unlike its news brethren. Pemsel’s big push: link the passion of the brand with making money. Wait a minute: You thought The Guardian wasn’t supposed to make money? That’s the sometimes bizarre atmosphere Pemsel says he walked into when he joined up. The ambivalence about making money surprised him and more: “aghast, horrified, and shocked” were the words he used. Somehow, The Guardian’s penetrating, crusading journalism and the “open” editorial strategy espoused by editor Alan Rusbridger had overwhelmed the rest of the business in how it was perceived, and sometimes in how it operated. Pemsel says he’s been at pains to correct his biggest advertisers and agency clients: The Guardian isn’t a nonprofit. (Legally, it’s a for-profit, with a single shareholder: the Scott Trust Limited, which is legally charged to reinvest profits to “sustain journalism that is free from commercial or political interference.”) The problem Pemsel found in the ad community wasn’t a matter of legal definitions. Rather, it was: If you’re going to sell million-pound campaigns, you’d better be seen as a business. “We had to scrap our way to commercial credibility,” Pemsel says. Some numbers say The Guardian is headed in the right direction. It reports its results only annually. Through last March, it showed a 29 percent increase in digital revenues to £55.9 million (or $91 million), growing at twice the rate of the digital ad market. Look for similar results when it reports again in June. The reasons: unprecedented high-level engagement with top brands and agencies, like telco EE and Unilever, and a new generation of revenue out of native ad-oriented Guardian Labs. Like its peers, The Guardian has moved to an audience-based sales approach that is pulling in bigger campaigns at good rates. But that digital ad growth is just offsetting print declines. Even though The Guardian managed to gain print readers recently, it is of course seeing the same kind of print ad drop as the rest of the industry. Significantly, it doesn’t have an overarching paywall strategy (though it charges for some tablet and smartphone app access). So it’s been the digital ad increase that has been responsible for helping get the company to flat revenue — unlike, for instance, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the Financial Times, which have used digital and all-access subscriptions to make up for print losses. As a whole, The Guardian stands at roughly that magic number of zero revenue growth (“The newsonomics of zero and The New York Times”), looking to shift into growth mode. In survival mode not long after taking his post in mid-2010, CEO Andrew Miller laid out a five-year plan for turning the company’s losses around. Even with the Scott Trust structure, Miller said that The Guardian could run out of money in five years if it didn’t change its ways. Since then, much has changed, though there’s lots more to be done. Staff is The Guardian’s No. 1 cost, of course, and there have been layoffs, right-sizing, and other cuts. One goal of the five-year plan: cut £25 million out of the newspaper cost base by the end of the 2015-16 fiscal year. Most significantly, last month Miller pulled off his long-awaited coup. He sold The Guardian’s 50.1 percent stake in the auto-dominated Trader Media Group to minority owner Apax, for £600 million ($985 million). Miller, who had headed TMG before moving over to The Guardian, has one big asset left to sell, the TRG group, in which it owns a 33 percent share. (David Worlock provides a good backstory on these investments.) The Guardian — just like The New York Times Company — is slimming down to its core asset, having sold off radio, a property services group, the legacy Manchester Evening News, and more over the past several years. For both the Times and The Guardian, the game is simple: A singular, global news strategy. One big bet on the future. When the Trader deal closes, likely by month’s end, it won’t just provide The Guardian money — it’ll buy time. Time, in this era of rapid transformation, is the key. How much time and how the proceeds will be invested are still open questions. While The Guardian gains a big nest egg, it loses Trader’s contribution to profit and revenue, and will do the same when it sells its TRG stake. Without those contributions, The Guardian continues to lose money. Under Miller, it has cut those losses, but the news group itself — Guardian News and Media, made up of the daily Guardian and the Sunday Observer — lost £30.9 million last year. Consequently, for Miller and for Pemsel, the five-year march is still on, now in Year 3. Therein lies the Known Strategy. On one hand, we have the fruits of The Guardian’s journalism and its strategy of ubiquity. “Open journalism,” available free on many platforms, feeds traffic. The new country-specific sites in the U.S. and Australia multiply traffic. The Snowden scoops pour in lots of new readers. All together, The Guardian draws in about 40 million unique visitors a month, about two-thirds of them outside the U.K., though, of course its U.K. readership is the most engaged. In traffic, it’s competitive with the global reach of The New York Times and Mail Online. Registration is the glue in the middle: getting readers to reveal something of themselves, then more over time. To the extent they do that, they move from being unknown hordes to potential buyers of…something. Then there are all the ways The Guardian could — and might — monetize an increasing percentage of those 40 million. We start with the 180,000 or so who pay The Guardian for something other than advertising. We get to the 180,000 number by adding The Guardian’s print subscribers (not counting its heavily single-copy buying readership) to those paying for its individual mobile apps, sold at differing price points on different continents. In my mind, that’s still the best way for publishers (and journalists) to get paid. Beyond that, there are these current Guardian businesses:

That’s today. The big open opportunity is membership. Pemsel has hired David Magliano to be managing director for membership strategies. A Guardian membership program, one that contains some audacious elements, is in the planning stage, but details are still confidential. It’s got to be audacious: Without a paywall — the way the FT, the Times, the Journal, and now hundreds of local dailies have turned digital readers into known quantities — The Guardian has unprecedented outing-of-the-anonymous-masses work ahead of itself. Paywalls have been effectively used in two ways by publishers to get to know more about once fairly unknown readers: (1) incentivizing and cajoling print subscribers to register/authenticate themselves online, and (2) earning registration as an interim step toward subscribing — a practice the FT, in particular, has perfected. Without the paywall, The Guardian’s membership pitch will have to be especially meaningful. But if The Guardian can get one or two or five percent of unique visitors registering for some level of free or paid membership, then it can multiply its revenue from services and products. “Known,” then, isn’t a blindingly new strategy — but in a single syllable, it brings a bracing clarity to what news publishers must do to compete in a world of data, analytics, and programmatic ad selling, led by Google and Facebook. Only by winning over, serving, and deeply knowing their customers, will publishers find the business models to sustain themselves. Like most publishers, The Guardian is reliant on advertising for a majority of its revenue. And like most execs, David Pemsel knows that even with all he’s doing to win the digital ad game, consumer direct revenues must be a big part of The Guardian’s five-year-and-beyond plan. Unique to the challenge of The Guardian, with its open philosophy and paywall-eschewing strategy, is a way to leverage The Guardian’s “open” vision into a differentiating commercial strategy. The Guardian can hope that in Pemsel, it has found the right partner for Alan Rusbridger — one who can turn openness into commercial success. At this point, Known is at its beginning, and playing catchup to some of its peers whose strategies have already netted them hundreds of thousands of known customers. It’s a parcel of good ideas in search of substantial reader revenue. It seems directionally correct, and that’s an achievement for a company whose editorial excellence has thus far surpassed its business savvy. Membership does offer vast potential, but it’s unproven; no news publisher has yet cracked that egg. It would be great if The Guardian could directly get its digital readers to pay up more directly. But it remains unconvinced in the value of paywalls; its paid apps still seem to me to be a scattershot approach. Andrew Miller and David Pemsel, though, could be right: Membership — if smartly executed — could produce even bigger dividends than current paywalls. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |