Nieman Journalism Lab |

- The Washington Post goes national by offering free digital access to readers of local newspapers

- The nonprofit Africa Check wants to build more fact-checking into the continent’s journalism

- The unfaithful audience: How topics, devices, and urgency affect the way we get our news

| The Washington Post goes national by offering free digital access to readers of local newspapers Posted: 18 Mar 2014 08:43 AM PDT

But the Post has a new twist on that old debate. The paper said Tuesday it will begin to offer free digital access to its websites and apps to subscribers of a number of local newspapers around the country in an attempt to reach a larger digital audience — and signaling that the paper is moving to position itself as a major national news brand. The Dallas Morning News, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, The Toledo Blade, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel will be the first papers to participate. The program launches in May and would seem to be a win all around: Local papers get a significant new benefit to offer subscribers; the Post gets extra premium audience online and likely doesn’t lose many (if any) marginal digital subscribers. And it’s a model that could, if successful, be expanded at near-zero cost to dozens or even hundreds of other dailies. And the idea of a Post digital subscription as a throw-in benefit opens up lots of new possibilities. The Post could potentially work with other subscription services like Amazon Prime, Spotify, or others to offer digital access to the Post, Washington Post president Steve Hills told the Financial Times. He also said that the strategy, one of the first major initiatives launched since Jeff Bezos bought the Post last year, is a substantial shift in how the paper approaches its business.

At this writing, a new digital subscription to the Post goes for $3.99 every four weeks or $39 for a year, although prices can vary depending on current offers. The paper launched its metered paywall last summer. [Update: The Washington Post's communications staff would like you to know that the price for a digital sub is $9.99 a month for web only or $14.99 for web plus apps. That's despite this screenshot right here, linked above, that clearly shows a $3.99/month offer. Here's the full page. I reached that page through the obscure method of clicking the "SUBSCRIBE: Digital" link at the top of the homepage. —Josh] Bezos is known for not worrying about profit margins, and the FT reports that no money is changing hands as part of the partnership with the six local papers. |

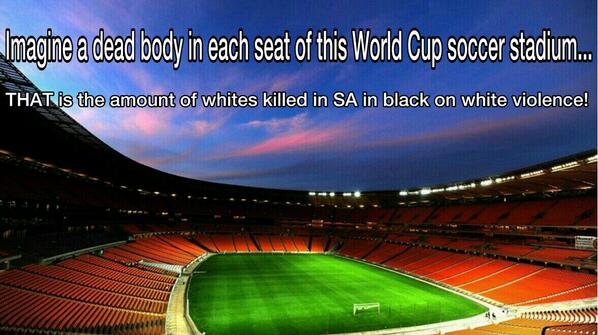

| The nonprofit Africa Check wants to build more fact-checking into the continent’s journalism Posted: 18 Mar 2014 08:17 AM PDT The words are superimposed over a photo of a soccer stadium sitting empty at dusk: “Imagine a dead body in each seat of this World Cup soccer stadium…THAT is the amount of whites killed in [South Africa] in black on white violence!”

South African singer Steve Hofmeyr posted that image last June, accompanying lengthy claims on his website and his Facebook page that white South Africans are being “killed like flies” across the country. And with more than 200,000 Facebook followers, the posts drew a fair amount of attention throughout South Africa, which has one of the highest murder rates in the world. But were Hofmeyr’s claims accurate?

Founded in 2012 by the Agence France Presse Foundation, Africa Check is a nonpartisan outfit with the dual goals of checking the veracity of public statements and educating journalists across Africa on how to approach fact checking. “I was not setting out to prove Steve wrong — I was setting out to understand the claims he was making,” said veteran South African reporter Nechama Brodie, who freelances for Africa Check and wrote the report last summer debunking Hofmeyr’s claims — which generated an outpouring of both public support and derision. Africa Check’s mandate is to cover the entire continent, but with a small staff, its initial coverage has mostly been focused on South Africa, where it is based. It’s taken on subjects ranging from South African President Jacob Zuma’s State of the Nation address to whether the filming of the movie Long Walk to Freedom, based on the life of Nelson Mandela, really “sustained” 12,000 jobs over two years. (It did not; nearly 11,000 of the claimed jobs were extras who worked an average of two days each.) Led by dedicated efforts such as PolitiFact and FactCheck.org and more aggressive work at traditional media outlets, fact checking rose to particular prominence in the United States during the 2012 presidential election, but the concept is relatively new to African journalism, according to Peter Cunliffe-Jones, deputy director of the AFP Foundation and founder of AfricaCheck. “Fact checking isn’t an easy practice in the U.S. or the U.K., but I think it operates in a different environment in Africa, where it simply isn’t as easy to get a hold of the data and the quality of data you get a hold of is more questionable,” said Cunliffe-Jones, noting that there is not as strong a culture of freedom of information across much of Africa as in many Western countries. “Not simply reporting what people say”Cunliffe-Jones, a Nigeria-based correspondent for Agence France-Presse for five years, said he first realized the need for more fact checking among African journalists in the early 2000s after UNICEF and the World Heath Organization launched a campaign that they’d hoped would be the final push to eradicate polio in west and central Africa — with a focus on Nigeria, where most of the cases were originating. The plan failed. Leaders in states in northern Nigeria were able to lead a boycott of the polio vaccinations that was driven by news articles that reported the leaders’ misleading comments on the effectiveness of the vaccine and its potential side effects. And with Nigerian cases left unaddressed, some of the infected traveled to other areas of the world where polio had previously been eradicated. If the false claims made about the vaccine had been properly debunked by journalists, polio might not have spread as easily or as far, Cunliffe-Jones said. “That seemed to me, to be a classic case of, had the journalists quickly investigated the claims that the governor of what was the largest northern state there, Kano, was making and exposed the fact that it was specious, potentially you could have eradicated polio with the efforts of UNICEF and the WHO,” said Cunliffe-Jones. “It’s a very practical example of the failure of us as journalists to carry out our fuller, proper duties of not simply reporting what people say, but looking into them.” So after joining the Agence France-Presse Foundation as its deputy director in 2011, one of the first initiatives Cunliffe-Jones undertook was to launch Africa Check. Inspired by the likes of PolitiFact, Africa Check launched in 2012 with six months’ worth of seed money from Google, which it won through a competition run by the International Press Institute. Housed in the University of the Witwatersrand’s journalism department, Africa Check has three full-time staffers plus Cunliffe-Jones, who works out of the U.K. The organization has been able to obtain sustained funding and now has aims to grow. Africa Check’s content is frequently republished, without charge, in a number of publications in South Africa and other countries. The group’s arrangements with outside news organizations allows it to spread its message and ensures more readers see its content beyond the 50,000 to 60,000 unique visitors who come to AfricaCheck.org each month. The Mail & Guardian is one of the South African publications that publishes Africa Check’s content fairly regularly, and editor-in-chief Chris Roper said working with Africa Check allows the paper to publish thoroughly researched investigative pieces without expending reportorial resources that are already devoted elsewhere. “Generally with us, and other South African newspapers, you have a volume of content you have to cover, whereas Africa Check can really focus on individual examples,” Roper said. Africa Check’s initial focus on South Africa was prompted by the greater availability of data and information readily available there, Cunliffe-Jones said, but he added that the organization plans to expand to other areas of the continent, with the aim of even starting a French-language version for francophone West Africa. “If we were going to be starting this up, we wanted to do it somewhere where we would be able to learn the ropes of doing this, in a place where it was easier to do it than in, say, the Democratic Republic of Congo or somewhere,” said Cunliffe-Jones. “From there, the aim is to start running reports from Nigeria. We’re hoping to go to East Africa as well.” Providing an educationBut no matter how large Africa Check gets, it’s unlikely to ever cover the entire continent by itself — which is part of the reason for its strong emphasis on the educational components of its mission. “It would simply be too big to think of one website that has an operation in each and every country,” Cunliffe-Jones said. “That’s not the aim. The aim is more to provide an example that can be seen and that can then serve as a spark, as a catalyst, to both promote the idea of fact checking and to help support and enable others in the media and in civil society to do it for themselves.” On its website, Africa Check publishes a number of guides and other resources to help teach people, both journalists and non journalists, how to fact check. They range from more general skills, such as “how reporters can ensure accuracy in their writing” to country-specific tools, like an overview of how to interpret South African crime data. “Crime statistics are released every year, and they’re misinterpreted every year,” said Brodie, who also wrote Africa Check’s guide to understanding them. Because of its location within the journalism school at the University of the Witwatersrand, it’s also able to provide hands-on education to journalism students who can work with the project. “Africa Check embodies a range of important journalistic values: accuracy, independence, scepticism, questioning,” Anton Harber, director of the university’s journalism program wrote in an email. “I believe students are more likely to imbibe such values by doing work for Africa Check and seeing its impact than if we stand in front of them and lecture them on these things.” |

| The unfaithful audience: How topics, devices, and urgency affect the way we get our news Posted: 18 Mar 2014 07:32 AM PDT When it comes to finding and consuming news, Americans are only as faithful as their options. A new report finds that how we consume the news is largely dependent on what we’re looking for, the technology at hand, and whether the story is urgent. Forty-five percent of US adults in the survey say they have no preference in device or technology for following the news. The report, “The Personal News Cycle,” the first from the Media Insight Project, looks at the ways Americans discover and consume news across platforms. The Media Insight Project is a collaboration and new partnership between the Associated Press, the American Press Institute, and the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. The group surveyed 1,492 adults over the age of 18, with 1,006 on landline phones and 486 on cellphones. The overall picture created by the survey shows Americans become more comfortable with media switching to get their news, as more than six in 10 American adults get news in a given week from each of television, a laptop or desktop, radio, and print newspapers or magazines. Not far behind: cellphones at 56 percent and tablets at 29 percent. And the news can now seek them out: The survey found that 45 percent of Americans have signed up for news alerts, including text, email, or app notifications. It’s worth reading through the whole report, but here’s a few highlights worth noting: News breaks on TV and finds context onlineTelevision remains a strong source for breaking news, with half of the respondents saying they first heard of a recent breaking story on television. But rather than stick with TV as the story progressed, 59 percent of people who wanted to follow up went to the web instead. But where they went online followed some traditional routes, including a surprising preference for the online sites of TV stations: 37 percent said they want to a TV news outlet (13 percent local, 12 percent cable news, 1 percent national network news, the rest unspecified), versus just 9 percent who went to newspapers. Another 10 percent went to online-only sites. Topic dictates mediumThe types of news you’re interested in might inform where you go looking. The survey found that Americans divide up their attention to different media depending on the news they want. On international news, government news, or stories on business and economics, cable news is king. For crime, traffic, and weather, most people turned to local TV. For town or city news, education news, or arts and culture, newspapers won out. In broader topics, like sports, entertainment, or technology, readers chose speciality publications. (In the study’s eyes, “specialty” media can include both online-native and legacy outlets.)

Trust and social mediaPlatforms like Twitter and Facebook have grown as outlets to discover news, but according to the report, four in 10 Americans say they got some news during a given week from social media. That behavior varies widely by age, though: It’s true of 7 in 10 adults under 30, 6 in 10 adults 30–39, 4 in 10 adults 40–59, and 2 in 10 for those 60 and above. Readers in the survey also tended to show some skepticism of social media compared to other sources of news. Only 15 percent of adults who get news through social media said they had a high level of trust in what they learn there; 37 percent said they only trusted it slightly or not at all. By comparison, 43 percent of those surveyed said they trust the information they receive directly from a news outlet. Adapting to the constant news cycleA plurality of respondents in the survey said they prefer getting news throughout the day rather than in the morning, afternoon, or evening. Similarly, a plurality of people in the survey said there is no particular time of day they prefer to read in-depth news. That runs counter to some data that suggests people reserve evenings for deeper reading time.

Young people and the newsThe report offers multiple data points to demonstrate young people are news readers and have a connection with the news. Eighty-three percent of adults age 18–29 say they enjoy keeping up with the news, and 56 percent say they consume news at least once a day. The report says young adults are three times more likely to find news on social media than those over 60; people under 40 are more likely to get news through Internet searches and aggregators than those over 40.

That print figure for young readers runs counter to data from elsewhere. In 2012, Pew Research found that only 6 percent of adults age 18–24 and 10 percent of adults 25–29 reported getting the news from a print newspaper. The numbers aren’t strictly comparable — Pew was asking about news consumption “yesterday” versus this study’s “last week,” and Pew asked about newspapers whereas this study includes news magazines. But nonetheless, they seem to reflect different realities. Photo by Timo Kuusela used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

In 1980, The New York Times

In 1980, The New York Times

They weren’t, it turns out, according to a

They weren’t, it turns out, according to a